F*cking with the Virtual

school of x in connection with xCoAx

class of 2023

Abstract

How do bodies incorporate networked technologies in their sexual experiences? F*cking with the virtual looks at “cybersex” from the 90s and early 00s to discuss how it has materialized through contemporary commercial sexual technologies: interactive sex toys, VR porn, and dating apps. Using a lens of affect theory, the three cybersex technologies at the center of the essay indicate a move in modes of interfacing: from the visual/textual to the immersive and finally to the interactive experience. In the early 2000s, cybersex was imagined as an immersive and mediated sexual experience facilitated by technological gadgets and wires. Those technologies have influenced cybersex technologies and their design today. This paper offers a brief survey of the history of cybersex technology, considering how to use affect theory and modes of interfacing to consider what cybersex can tell us about our past, present, and future intimate relations to technologies.

Keywords

Cybersex, Technology, Embodiment, Desire, Sexuality, VR Porn, Teledildonics.

Affect and virtuality in cybersex

What role do the body, embodiment, and sensation play when we have sex online? This paper explores instances where “cybersex,” as imagined in the 90s and early 00s, has materialized in contemporary commercial sexual technologies: interactive sex toys, VR porn, and dating apps. The three cybersex technologies indicate a move from the visual/textual (sexting) to the immersive (VR porn) and finally to the interactive (teledildonics), tracing not only the changes in the cybersex experience but also how contemporary technologies are directly influenced by techno imaginations of the past.

While, terms like affect, the body, cybersex, and the virtual have become slippery surfaces in theoretical encounters. I define cybersex as sex with and through technology, an erotic encounter that utilizes some form of technology to occur. I define affect,as sensation, an intensity experienced by both body and mind together following a Spinozist legacy, introduced by Gilles Deleuze and elaborated further by Brian Massumi and by critical studies during what Patricia Clough defines as the “affective turn” (Clough 2007, 1). It is crucial to think of the virtual as it relates to technology, cyberspaces, and VR/AR technologies through a lens of affect in an attempt to bring embodiment back into the technologically mediated landscape.

Intensity, sensation, and vibration become central in this approach as they allow sensation and affect to circulate between technologies and bodies, human and non-human agents.Expanding on this idea, affect is experienced on the body and through the senses; it is a visceral experience where mind and body are interrelated unity. Affect is a force, intensity, or flow that penetrates the body and increases or decreases its power and capacity to act. (Spinoza 2005, 70). Affect can be a valuable theoretical tool when considering cybersex because it can account for this centrality of sensation and the multiple transformations of desire, lust, stimulation, and vibration that moves between bodies and technologies.

Interfacing in Cybersex

In cybersex encounters, the human body appears entangled with different technologies to reach outward and extend, seeking another body, skin, vibration, message, or encounter. Thus, the body meets first with different technologies and each of them carries its own mode of interfacing. The interface or mode of cybersex shapes the experience of cybersex. For Alexander Galloway, interfaces can be screens, windows, keyboards, sockets, holes, or channels. It is only when they are in effect that interfaces can materialize and reveal what they are. In this way, Galloway defines as “the interface effect” the process of mediating thresholds of self and world (viii). The mode of interfacing between the screen/body determines how mediation operates and affects the online experience. How do we interface with technologies to connect intimately with each other?

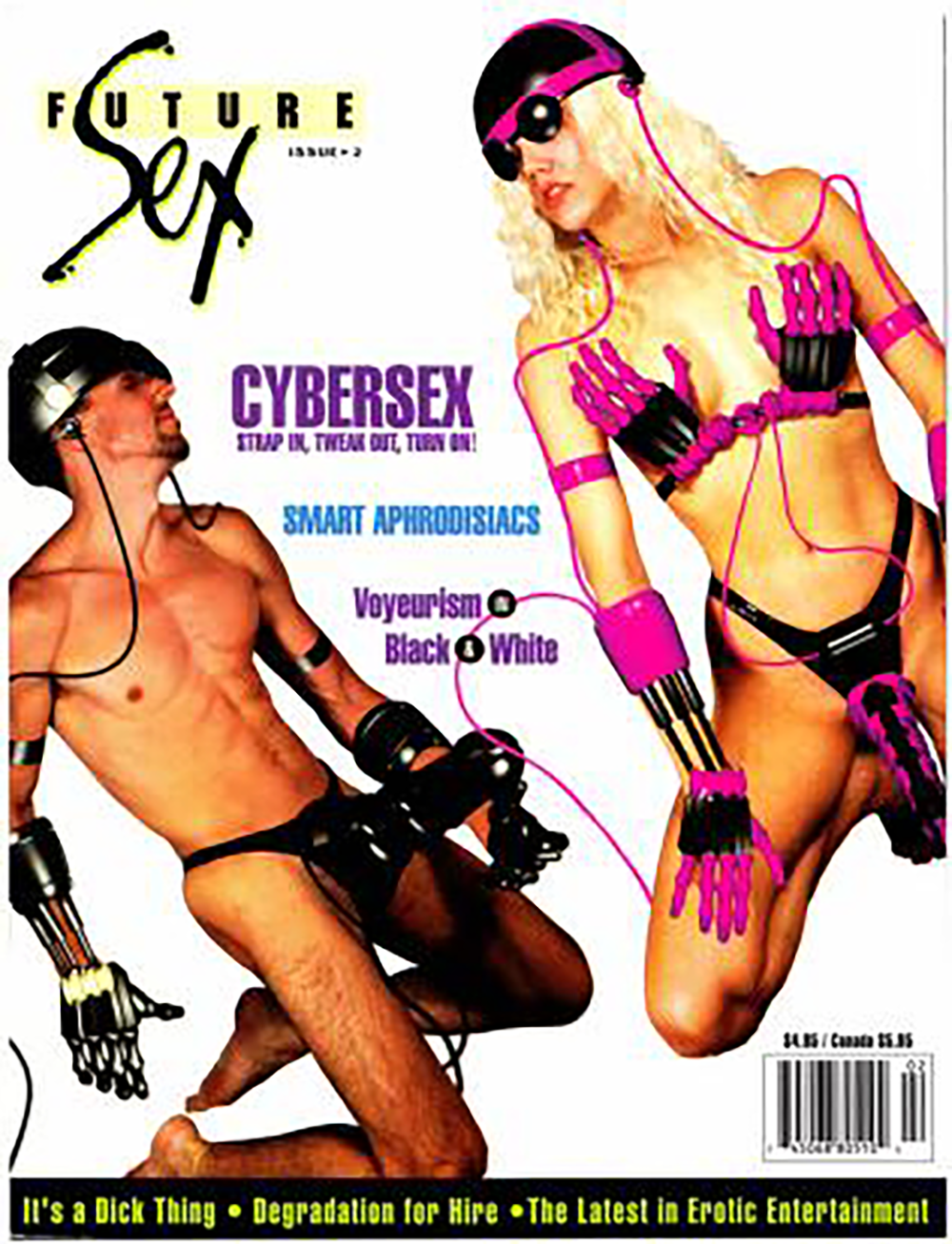

In the earlier techno-imaginaries of cybersex (fig.1), all modes of interfacing work in tandem and coexist to create a united experience, an immersive illusion of interactivity. Today, they have materialized not only as distinct technologies but as distinct modes of cybersex. Cybersexual interaction has moved from textual and audio communication to visual and audiovisual, to the promise of the immersive allowed in VR porn, to arrive into today's wireless interactive Bluetooth-enabled sex toys. The relationship between the body and the interface technology (whether a laptop, phone, VR headset, sex toy, or both) creates a bodily relationship in physical space.

The interface determines the rules of the interaction; it defines the affordances and the allowances of the communication, and how users relate to both the “experience” and the “screen.” In The Posthuman, Rosi Braidotti explores how the relationship between human bodies and technological others moves between intimacy and intrusion (Braidotti 2013, 89). Braidotti’s notion of “becoming machine” sees bodies and machines as intimately connected through simulation and mutual modification within a circuit of representation-simulation–biomediated bodies. The different modes of interfacing in cybersex structure cybersexual assemblages where affect transforms and reshapes itself as it moves between human and non human organs, cables, code, wireless connections, and more.

Following Braidotti’s ideas, a focus on the technologies of cybersex and how they come to touch with the human body allows us to move from disembodied cyberspace into an embodied sensorium where the body becomes the center of the experience. Cybersex crafts a unique setup where the body becomes vulnerable in front or next to technology while also disguised behind a nickname, a profile or VPN address. Still, there is a tenderness and a vulnerability the technology that controls and determines the modality and shape of our interaction.

Virtual Bodies in Cyberspace

To think of the body in cybersex, we first have to think of the body in cyberspace and Virtual Reality(VR). Who is the subject that is fucking with the virtual; sits in front of the computer; holds the smartphone swiping and sexting; takes nudes standing in front of a mirror; wears the VR headset to be immersed in a sexual, mystical journey in cyberspace; connects via Bluetooth connected sex toy to a lover far away. The mediated landscape of being online, and the technological tools that one engages with to access “cyberspace” have been completely transformed with the emergence of new technologies. Thus, our contemporary online spatial experiences and communities might not be similar to the cyberspace imagined in science fiction.

In The War of Desire and Technology in the Close of the Mechanical Age, Sandy Stone (1995) sees cyberspace as a social environment, one that allows interactions not only between people but also between humans and machines. Those interactions between humans and machines and humans to humans through the machine, allow a new identity to emerge. For Stone, cyberspace is “a space of pure communication, the free market of symbolic exchange–and as it soon developed, of exotic sensuality mediated by exotic technology.” (Stone 1995, 33)

Cybersex 2: Then and Now

In the 1990s, magazines like Mondo 2000 (1984-1998) and Future Sex (1992-1994) emerged as an intersection of cyberculture and sexual positivity influenced by cyberpunk fiction writers like William Gibson and Bruce Sterling. In their pages, cybersex was imagined as the future of sex, a combination of sex, drugs (mainly LSD), and future technology that create an enhancing simulation. A prevalent issue when thinking of cybersex in films, magazines, and cyberpunk discourse was how the sensations experienced by the virtual body in cyberspace could be felt on the physical body of the participant. Solutions come in many forms: Howard Rheingold imagines teledildonics (1992, 345), Kroker imagines electric flesh (1993), and films like “The Lawnmower Man” (1992), “Brainstorm”(1983), and “Live Virgin” (2000) envision cabled bodysuits, machines, and architectures that engulf the body so that they can mediate sensations from the cyberspace to the body that stands with/in or on the side of the device to experience cybersex.

In 1992, on the cover page of the second issue of the magazine Future Sex, we see two naked bodies, male and female, enhanced with different technological gadgets and wires: thongs with strap-ons, arms replaced with robotic arm suits, a wired helmet, and goggles connected with wires. Following the magazine's headline “Strap in, Tweak out, Turn On!” the two models are enhanced with technology to experience “Cybersex 2.” Michael Saenz and Reactor speculate how fabrics, sensors, immersive 3D technology, and tactile data would create erotic simulations without the dangers of human interaction (Saenz 1992, 28). The lovers' encounter occurs in cyberspace; the Virtual Reality headset offers access to cyberspace; the sensations experienced during cybersex are felt on the body through teledildonics and bodysuits. In this image, cybersex is imagined as an immersive and mediated sexual experience facilitated by various devices. This early image of cybersex highlights the centrality of the body and how it interfaces with sensory network technologies. The body becomes a mediator; the technologies allow the body to feel through sensory stimulation, an encounter in virtual cyberspace. Furthermore, it is the technologies depicted in this techno-imagination that are now thirty years later defining the future-present of sexual technologies. How have those fantasies of cybersex been realized today through specific technologies?

Screen to Screen and Peer to Peer: Textual, Visual, Audio

The simplest modality of cybersex is fostered as peer-to-peer interaction that takes place using text, sound, or images. From the phone to the computer to the smartphone, from the AOL chatroom to Second Life, cybersex seems to be experienced in writing (textual), in voice (auditory), in the image (through an exchange of images and or representational sexual acts within videogame). Technology acts as a mediator and interface between the two desiring subjects. The technology stands in-between them, creating an excitement of participating in a subculture that is dark, exciting, forward, and futuristic.

In “Romancing the Anti-Body: Lusting and Longing in (Cyber)space,” Lynn Hershman Leeson discusses how by default, cyberspace requests the user to create a mask, structuring a computer-mediated identity that might correspond or not correspond to reality. For Leeson, as users are asked to redefine themselves through names, profiles, icons or masks they are also determining their audiences spaces and territory. In this way “anatomy can reconstituted.” (Hershman-Leeson 1996, 325)

Research on cybersex often discuss the potentialities of assuming avatar anti-bodies online, well-crafted personalities that allow for each physical body standing in front of the computer to have multiple corresponding bodies in cyberspace. Users in Compu-Serves having compu-sex, users behind phones having phone sex, and users of Second Life, using their avatars to have cyber sex, share some similar experiences. Those experiences share the element of crafting new identities and creating desire-ing and desirable bodies. In the environment of the contemporary dating app, texting and exchanging images become a central element of communication. This time the smartphone touch screen becomes the central interface with which the body engages. This text and image-based sexual communication seem almost like a descendant of the anonymous space of the chatroom that proliferated in the early 00s.

Immersed and Strapped in: From VR Sex to VR Porn

In Virtual Reality , Howard Rheingold (1990) imagines virtual reality sex as a collaboration between virtual reality and teledildonics. Rheingold imagines that through the marriage of virtual reality and telecommunications networks, teledildonics would allow sexual stimulation to occur by reaching out and touching other bodies in cyberspace. By incorporating a lightweight bodysuit and 3D glasses (VR headset) one could have a realistic sense of visual, auditory and haptic presence (346), what Rheingold calls an “interactive tactile telepresence” (348). Contemporary VR porn utilizing a VR heaset and a stroker pairing the porn strokes to the toy through AI, is the closest thing we have to this immersive vision of cyber sex.

In the Foreword of Hard Core, Linda Williams (1989) positions pornography as a genre that moves the viewer's body in a particular way. Contemporary VR porn creates a spectacle of visual pleasure where the contemporary stroker allows the viewer's body to be moved in the rhythm of porn, making any VR porn experience interactive. The headset enables immersion, and the stroker promises that the immersion is not only felt on the body but is perfectly paired with what you are viewing: the flow of the porn is the flow of the stroker. VR porn technology promises you can “Feel what you see” in real-time.

At the same time, VR porn structures a particular form of gaze, an embodied male gaze. There are two ways of looking in VR porn. In solo films and girl-on-girl films, the camera is placed at a safe but close distance to the spectacle, creating a rather voyeuristic gaze of someone who is there looking at the scene from nearby. The 360 camera creates a fishbowl effect; at the center of the scene lies the action/spectacle of the female pornstar(s) who is the center of attention. Mainstream VR porn films place the viewer in the center of the action as an active participant embedded in the body of the male pornstar in the scene.

What is striking in mainstream VR porn is how the gaze is pinned on the body of the male performer, who wears the 360 camera. There is a body that limits the gaze. The particularities of this body dictate the gaze, how it is elevated, and how to participate in the scene. The hands of the male pornstar mainly stay on the side, only rarely participating in the sexual act. The phallus of the male pornstar becomes the interactive element, the point of touch between the spectacle and the immersion, as this body part gets stimulated by the stroker.

Interacting: From Teledildonics to Bluetooth Sex Toys

Beyond the immersive experience of VR porn, teledildonics today are also marketed toward couples in long-distance relationships. Bluetooth wireless remote control sex toys for couples in long-distance exemplify the concept of virtual sex, allowing couples to “feel each other” when they are apart. In advertisements and representations, Bluetooth sex toys are often advertised as a stand-in or proxy for a partner in a long-distance relationship. In the companies’ narratives, wireless sex toys can replace sexual experiences with a video call and a pair of interactive sex toys. Bluetooth sex toys are both toys but also a complex technology that allows affect, desire, and data to circulate.

Cybersex using interactive sex toys facilitates encounters between human and non-human sexual organs, wireless and Bluetooth connections, smartphones, screens, and satellites. The promise of sex across distances is enabled by the virtual but only through digital technologies: smartphones, Bluetooth-connected sex toys, modems, and more. In "Technology and Affect: Towards a Theory of Inorganically Organized Objects,” James Ash defines inorganically organized affect :

an affect that has been brought into being, shaped, or transmitted by an object that has been constructed by humans for some purpose or another (Ash 2015, 87).

Ash argues that there should not be an ontological distinction between organically and inorganically organized types of affect. Still, it is necessary to understand how affect travels and changes from matter to matter, from objects to waves to humans. At the end of the article, Ash nods towards how an object-centered account of affect can decentralize the human to think about affective design, objects, encounters, and their afterlives. This expansive theorizing of affect can allow us to better consider this relationship between bodies and machines in cybersex. Bluetooth sex toys viewed through a lens of affect and intra-action can allow us to think about how we embody and relate to technology to argue for the need to consider intimate affective assemblages constituted by humans and technological others or non-humans.

Cybersex and beyond

Our technologies have been completely transformed, but our futuristic cybersex fantasies look the same. As bodies interface habitually with devices that connect to the internet and store data in the cloud, our ideas of cybersex remain connected to their historical precedents. It becomes urgent, to explore the imaginations of the past next to the representations of the present to consider this concept of feeling the virtual or sensing the other, connecting intimately through technology to feel each other.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Keneth Cordray GROW Summer Dissertation Fund, the Arts Dean's Fund For Excellence and Equity scholarship, and the UCSC, Film and Digital Media Department Summer Research Award for making my participation in the School of X possible.

References

Ash, James. 2015. ‘Technology and Affect: Towards a Theory of Inorganically Organised Objects’. Emotion, Space and Society 14 (February): 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2013.12.017.

Braidotti, Rosi. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambrdige, UK; Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Clough, Patricia Ticineto. 2007. ‘Introduction’. In The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social, edited by Patricia Ticineto Clough and Jean Halley, 1–34. London; Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Galloway, Alexander R. 2012. The Interface Effect.Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA: Polity.

Kroker, Arthur. 1993. Spasm: Virtual Reality, Android Music and Electric Flesh. Edited by Bruce Sterling. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Hershman-Leeson, Lynn. 1996. Clicking in: Hot Links to a Digital Culture. Seattle: Bay Press.

Mondo 2000. 1989. Mondo 2000 - Issue 01 (AKA Reality Hackers Issue 07). The Internet Archive. Accessed May 2023: http://archive.org/details/Mondo.2000.Issue.01.1989.

Saenz, Mike. 1992. ‘The Cybersex 2 System’. Future Sex-Issue 02.. Kundalini Publishing. The Internet Archive. Accessed on May 2023: https://archive.org/details/Future.Sex.Issue.02

Stone, Allucquère Rosanne. 1995. The War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the Mechanical Age. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press.

Rheingold, Howard. 1992. Virtual Reality: The Revolutionary Technology of Computer-Generated Artificial Worlds - and How It Promises to Transform Society. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Spinoza, Benedict De. 2005. Ethics. Edited and translated by Edwin Curley. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin Books.

Williams, Linda. 1989. Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the Frenzy of the Visible. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.