Despite numerous applications in live performance, Artificial Intelligence (AI) seems to be employed as a passive element, not deciding nor actively shaping what happens on stage. I explore the possibility of AI as an active element, able to direct performance. To push this scenario to its limits, I suggest implementing AI in the “eterodirezione” (hetero-direction) theatre device, where actors are given their part through in-ear monitors. I discuss the two possible outcomes of the implementation, “asynchronous direction” and “synchronic direction”, and I focus on the latter, where AI composes dramaturgy and instructs the actors in real time. I finally discuss the major outcomes of this new device, concerning the nature of the performance, the human-machine interface and the role of the director and actors. AI and actors prompt each other, improvising in a prompting loop, where they both become co-directors and co-performers of the performance, whereas the human director acts as a demiurge-like figure. This contribution is thought of as the first theoretical framework in the process of creating a new theatre language where AI is an active element of performance.

Artificial Intelligence, Theatre, Hetero-Direction, Synchronic Direction, Prompting Loop

Automation and machinery have long fascinated theatre-makers and found extended applications. In Stifter Dinge1 (2007), Heinrich Goebbel realised a fully automated live music performance staging complex machinery, which led scholars to speak of “Robot Opera” (Sigman 2019). In 2020, the Copernicus Science Centre in Warsaw opened the first “Robotic Theatre” in the world2.

Similarly, AI has drawn the attention of performance artists. In February 2021, “the first computer-generated theatre play” was staged as part of the THEaiTER project3 (Rosa 2020). Numerous other examples of applications have already appeared, where employed databases are either pre-existing, specifically designed for the performance or generated by discretisation of scenic elements. Among these are Corpus Nil4 (2016) by Marco Donnarumma, and Discrete Figures5 (2018) by Elevenplay, Rhizomatiks Research and Kyle McDonald. In the former, AI synthetises sonic elements after elaborating signals collected via microphones and electrodes installed on the performer’s body. In the latter, human performers interact onstage with pre-rendered 3D figures whose movements are generated by AI after the elaboration of a video database of human performers’ dance sequences (Befera and Bioglio 2022). In her interactive meta-drama AI6 (2021), Jennifer Tang stages over multiple evenings the creation of a play through GPT-3 (Akbar 2021).

In the above examples, AI seems to be employed as a mere tool, namely as a pre-scenic instrument to compose a dramaturgy or a movement sequence (as in the THEaiTRE project, AI, and Discrete Figures) or as an on-stage complement translating into sound, light or scenography (as in Corpus Nil). AI outputs are therefore either controlled and preventively collocated in the global dramaturgy or allowed to have an impact on the performance in real-time within pre-set limits. This is consistent with the ongoing debate on Generative Art, tending to refute AI autonomy in the creative process (Hertzmann 2018). The concept of “Meaningful Human Control” (MHC) applied to Generative Art (Akten 2021) strengthens this view, configuring “generative AI as a tool to support human creators”, who are the only agents accountable for the creative output (Epstein 2023).

Nevertheless, I argue that in Generative Art, AI seems to exhibit a certain degree of autonomy. After an initial prompt by the human user, the AI software is responsible for the image synthesis: what happens “inside the machine” cannot be monitored and the output cannot be foreseen. AI exhibits active features. In theatre, no examples have yet emerged where AI is employed as an active element shaping, creating, and ultimately directing the theatre performance. The above-mentioned projects show in fact that AI can contribute with a certain degree of agency and unpredictability, for example synthesising sonic elements, but cannot fully decide what happens onstage. A notable exception is represented by the Improbotics experiment7, an improvising device where AI provides lines to the actors. However, the presence of “free-will improvisers” not receiving lines from AI, and the restriction of AI intervention to textual dramaturgy eventually limit in my view its autonomy on stage.

In this essay, I address the question of whether and to what extent AI can have an active role in theatre performance, in the sense outlined above. To answer this question, a way of introducing AI in theatre performances needs to be found, that results in AI shaping the performance and maximizing its agency. I identify an already existing performance device to be implemented with AI and discuss the main consequences arising from this operation. My contribution aims to serve as a theoretical attempt to framework AI implementation in theatre and to shed light on some interesting aspects: concerning AI research, it helps to clarify the role of prompts and embodiment in the human-machine interface; from a theatrical standpoint, it helps to reaffirm the role of the human in a world progressively centred on virtuality. Ultimately, this essay is intended as a “declaration of intent” towards the creation of a new language in the performing arts, with further theoretical and practical studies intended as the natural follow-up.

I suggest as a base of exploration the method of “eterodirezione” (“hetero-direction”) invented and developed by the Italian experimental company Fanny&Alexander. Hetero-direction consists “in having the performer receive the directions for his or her part in the scene through an earpiece” (Di Bari 2021). The performer plays “lines and actions ‘administered’ by the directing division” without having to learn them by heart and without knowing the exact order of their part. This results in preventing “the routine and repetitiveness” inbuilt into the theatrical act (Margiotta 2020, my translation).

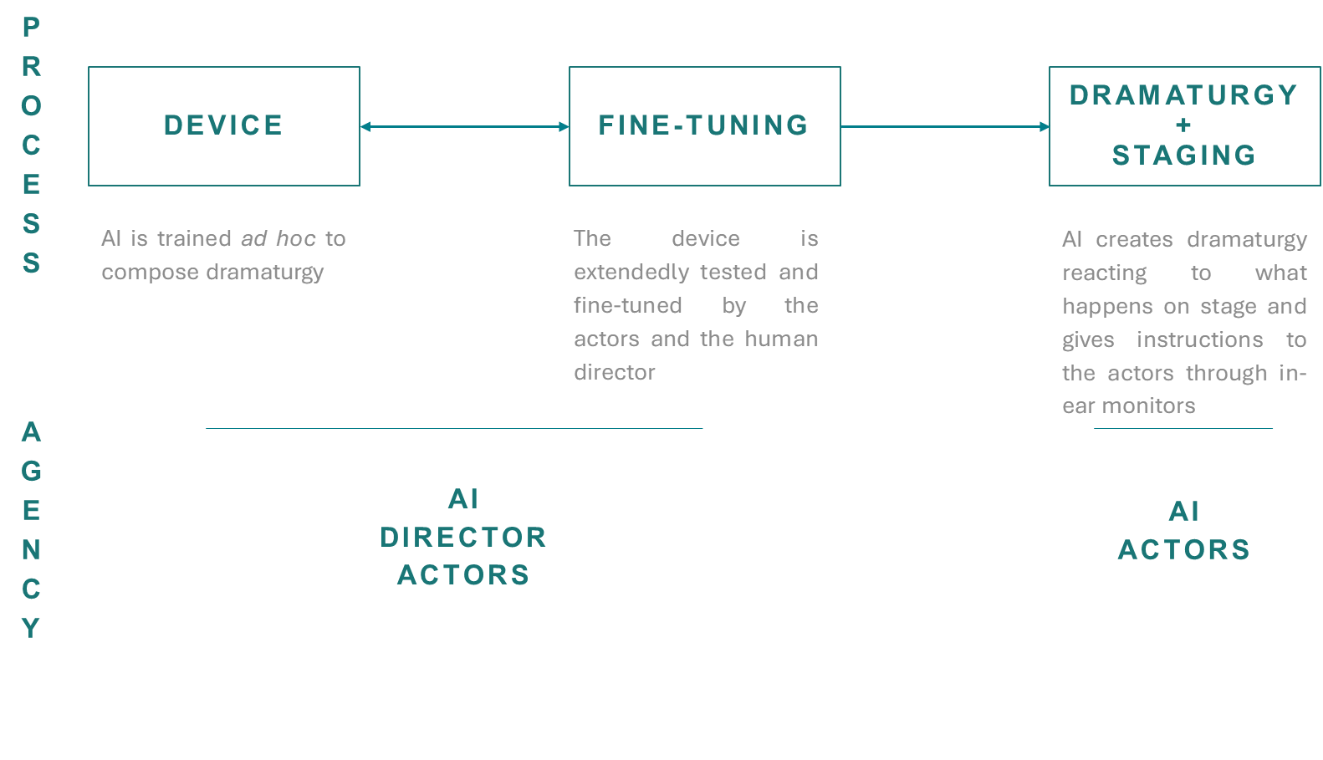

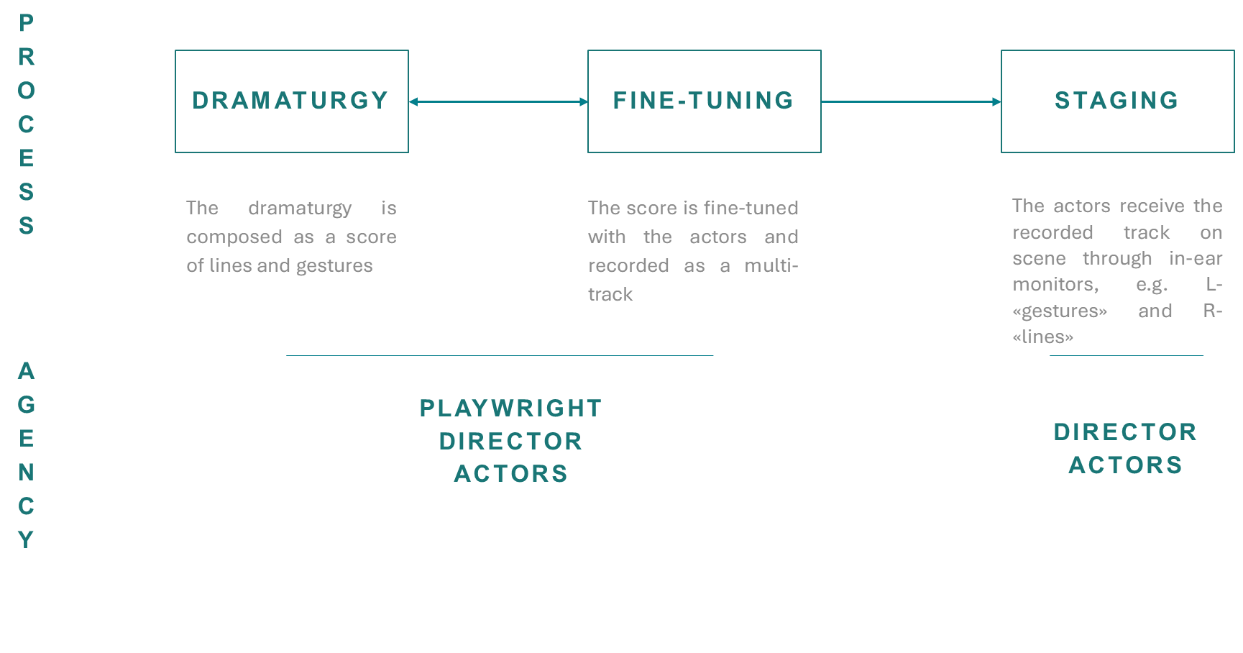

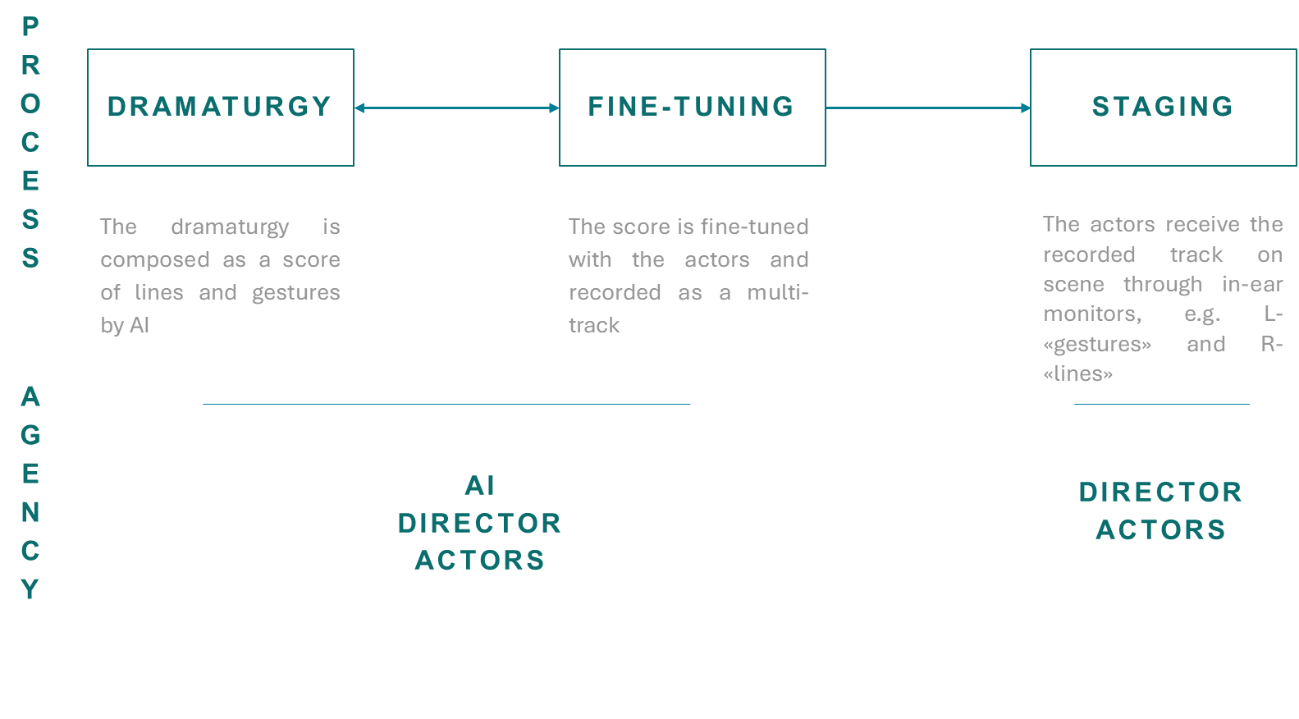

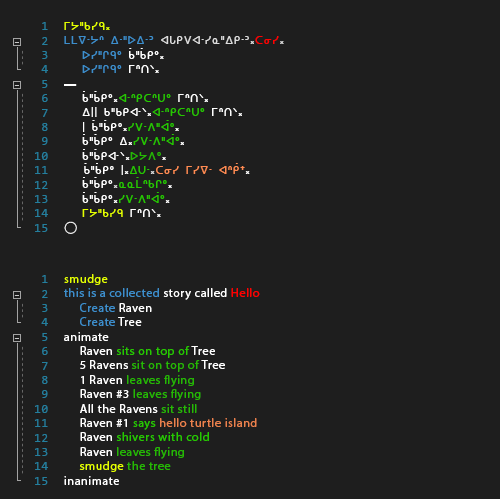

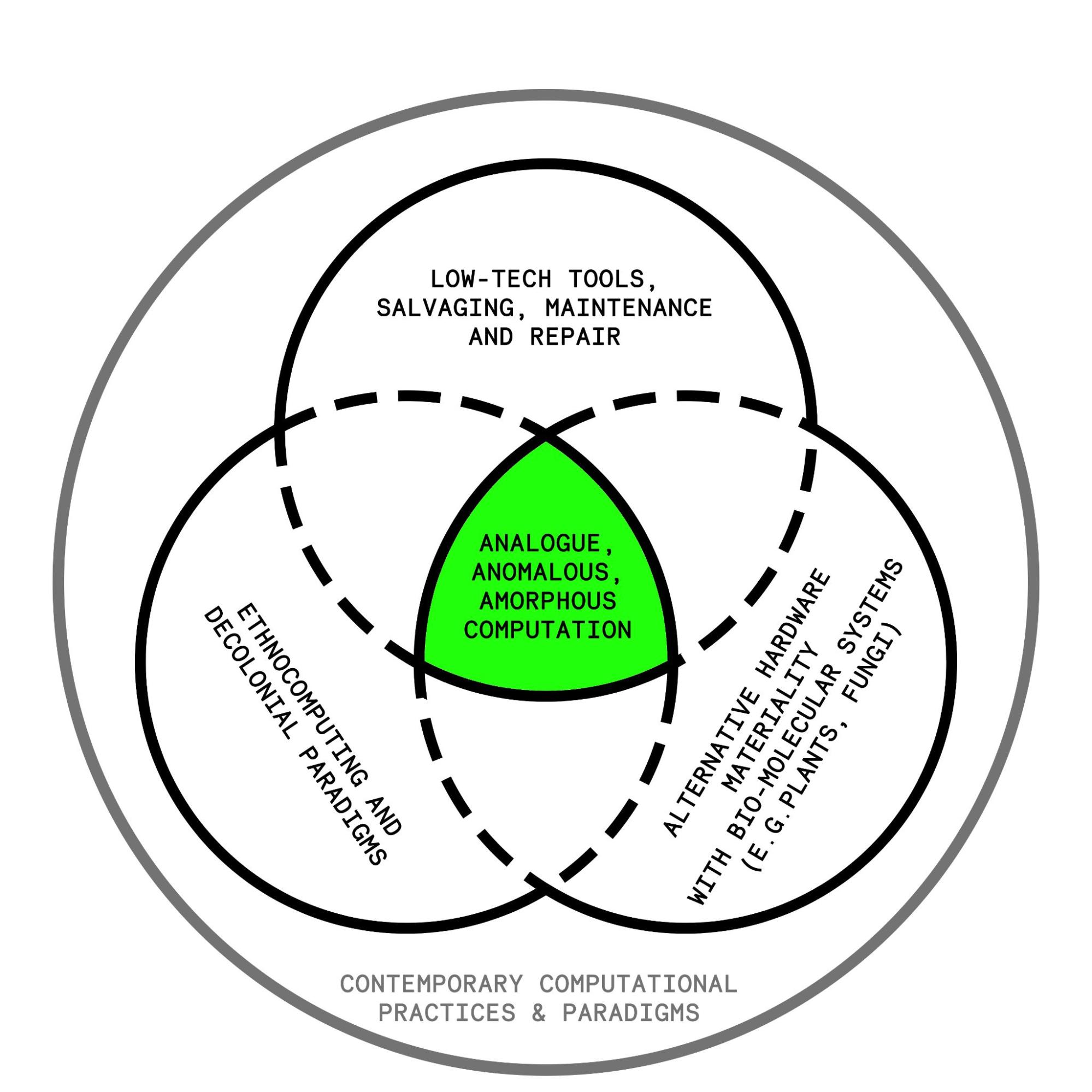

A closer look at the method provides useful insights into the possibility of AI implementation. I identify three phases of the creative process, summarised in the scheme of Figure 1, which will serve as a reference for the next sections. As it is common in theatre practice, “dramaturgy” can hereby refer to a broad variety of performance components, ranging from text to music, light, and space design. To point out the distinctive features of hetero-direction, I will henceforth limit myself to the dramaturgy as text and as a sequence of movements or physical actions.

In the first step, the dramaturgy is composed by the playwright and/or director and/or actors as a textual and/or physical score. The latter usually takes the form of a detailed (textual) list of precisely (physically) coded gestures, with a correspondent identifier name, which the actors will memorize as a physical “vocabulary”.

The score is then rehearsed and refined with the interpreters.

During the live performance, staged by the director, the set of instructions is transmitted to the actors through earphones, either through live dictation or as a pre-recorded track, e.g. with instructions for gestures recorded on the L-channel and instruction for lines on the R-channel (Margiotta 2020).

In my view, introducing AI may result in further developments of the device and in AI exhibiting an active role in live performance. I argue that AI can be introduced in hetero-direction in two ways:

In asynchronous direction, AI takes the function of the playwright in Figure 1: the whole dramaturgy is partially or totally written beforehand by AI and subsequently transmitted to the actors through real-time dictation or as a pre-recorded track. AI is employed as a mere tool and stage direction falls within human competence.

In synchronic direction, AI creates the dramaturgy during the live performance, reacting to what happens onstage and giving the actors real-time instructions. In this scenario, AI is present at all stages of Figure 1 and eventually directs the performance.

In asynchronous direction (see Figure 2), the hetero-direction scheme outlined in the previous section undergoes no relevant changes: the dramaturgy is composed in the first step, rehearsed, and fine-tuned by the director and actors and eventually transmitted onstage to the interpreters. The only difference consists in the implementation of AI in the first step. As we have seen in Section 1, both the composition of a play and of sequences of movements by AI have been proven possible. Nevertheless, in asynchronous direction, the result of AI implementation is analogue to that encountered in THEaiTRE or in Discrete Figures: AI is employed as a tool and does not actively direct the performance, which is ultimately staged by the human directing division. Moreover, it is likely the AI component would not easily be noticeable to the audience since the staging is entirely human-driven. For these reasons, I consider this option less interesting and will focus on the second one.

Since the dramaturgy is composed by AI onstage, in synchronic direction (see Figure 3) the original scheme is drastically changed, although the three moments of design, tuning and staging are preserved:

In the first step, the device needs to be designed and set into place. This means programming and training an AI model to detect and react to all the scenic variables while composing new dramaturgy and instructing the actors. A whole technological apparatus needs to be put in place, allowing AI to perceive what is happening onstage, for example through a scene-mapping mechanism made up of microphones, cameras, and sensors. AI could therefore recognize which positions are occupied onstage and react with an “if…then” logic, such as: if actor 1 is in A, then actor 1 goes to C and says “potato”.

In the second step, the functioning of the whole device is tested and fine-tuned by the director and through interaction with actors. Given the complexity of the apparatus, steps (i) and (ii) are likely to be performed in a loop every time a major difficulty arises during rehearsals, until the device is stable and does not jam.

The third step consists of the final performance. Here, staging and dramaturgy creation overlap. AI composes the dramaturgy and gives instructions to the actors, which perform them, providing in turn material for the AI to react.

The uniqueness of this scenario is evident: the AI is not anymore employed as a tool or a complement but is actively shaping the live performance, to the extent that it could be argued to be the actual director. This scenario entails several consequences on both a theoretical and practical level, some of which I am addressing in the next sections. I will focus on the nature of a performance realised through synchronic direction, the role of the human component, prompts and creativity.

Fabian Offert points out two interesting commonalities between theatre and machine learning (ML) (Offert 2019). On the one hand, they both “focus on discrete state transformations”, i.e. the transitioning between fixed states (be they machine states or those resulting from the composition of scenic elements) inside a “black-box assemblage” corresponding to the mise-en-scene in theatre and to the machine set-up in ML. On the other hand, they must both deal with an external singularity element they need to make sense of. Some theatre states are in fact “probabilistic”, insofar as they are affected by an external influence, such as improvisation or the presence of the audience. ML must instead extract “probability distributions from […] real-world data”. Accordingly, they are both connecting their “black-box” assemblage with the outside world, to “make sense” of it. Quoting Offert:

What theater and machine learning have in common is the setting up of an elaborate, controlled apparatus for making sense of everything that is outside of this apparatus: real life in the case of theater, real life data in the case of machine learning.” (Offert 2019, his italics).

In synchronic direction, not only are theatre and ML exhibiting this common feature, but they are also connected in a loop. This is clear when considering the nature and role of the prompt in this device. In Generative AI models, prompts usually consist of text lines which trigger a cascade of untraceable AI processes and result in a textual or image output. In our case, instead, the prompt is a physical component that is captured and quantised by the technological apparatus: the actors’ blood pressure or voice, a position in the space, etc. In a word, the body is here the prompt. The process, though, does not end here. AI elaborates the input, synthesises new elements of dramaturgy and instructs, i.e. prompts, in turn, the actors. Synchronic direction works therefore as a prompting loop.

In such a system, what is the singularity element pointed out by Offert? I argue that theatre and ML constitute the singularity source of one another. For theatre (the actors), singularity comes from the untraceable processes of AI and the unpredictability of its output. For ML, singularity comes from theatre and from all the external elements that can influence a theatre performance. This is where the role of the actor becomes clear. One could argue that synchronic direction flattens human creativity and reduces the actor to a “mere tool”, a puppet manipulated by AI. On the contrary: the actors bring into the device all the unpredictability inherent to their being human. As every dancer moves in the same choreography in a personal way, interpreting the pre-established sequence of movements through their own peculiar sensibility and body, so in synchronic direction will the actors perform AI instructions according to their own individuality. Moreover, their creativity will be solicited by the unpredictability of AI outputs. The same AI prompt results in different human outputs depending on who is performing it: different reactions will result in different quantised signals, triggering AI in different ways. As a result, human creativity is preserved, if not enhanced, and actors and AI are co-improvising, co-directing, and co-performing together. Coherently with the concept of a prompting loop, AI is not only directing but also performing and actors are not only performing but also directing.

It is worth noting that the prompting loop also highlights the uniqueness and irreplaceability of the human onstage. A synchronic direction device where no actors were involved, or where actors were replaced by robots, would arguably have no singularity other than the audience element or unlikely external events. This would result in the AI prompting itself or some entities designed to repeat the same task mechanically, always in the same way. Without a human being onstage, the performance would soon lose its driving force, which ultimately lies in the unpredictability of the human.

The role of the human director in synchronic direction is left to discuss. It appears that, in a prompting loop, no place for a director is envisaged. Indeed, I argue that the role of the human director is mostly limited to the design and rehearsing phase and is of a different nature than the conventional one (i.e. the “omniscient creator” of the performance). To recall the analogy with Generative AI models, the human director acts in our case as a hybrid between a technologist, an engineer, and a supervisor. They are the figure who coordinates the apparatus setup, verifies its functioning and its interactions with the actors and set the limits for the performance staging. To prevent the performance from degenerating into a non-sensical improvisation, rules need in fact to be established, concerning for example the overall dramaturgical context or “topic”, the rhythm and state transition frequency, the allowed thresholds of sound and light effects, etc. Retrieving a definition often encountered in the history of theatre direction, the human director acts here as a clock-maker or as a “kind of a demiurge” (Artaud 1958). Nevertheless, the director has no standing in what happens onstage and what the audience is going to watch, since only the two elements of the prompting loop, the actors and AI, are co-directing and co-performing onstage.

In this essay, I attempted to frame theoretically the implementation of AI in theatre and to set the ground for practical experiments. My interest was to understand to what extent AI can become an active and directing entity in live performances. To push this possibility to the limit, I proposed to implement AI in the “hetero-direction” device and focused on one of the possible outcomes, which I called “synchronic direction”. Here, AI composes dramaturgy and instructs the actors in real-time: AI can indeed direct a performance actively. A closer look at this system helps to clarify the role of the human in the device and, overall, in live performances. Considering the prompting loop: (i) human unpredictability appears to be an unavoidable element of performances; (ii) creativity is preserved, if not enhanced; (iii) actors and AI co-improvise, co-direct and co-perform onstage; (iv) the human director represents a demiurge-like figure.

For clarity purposes, however, dramaturgical elements such as space, light and sound design were not considered and shall be included in further developments of this model. The role of improvisation, which appeared to underlie the human-AI onstage interaction, is also to be clarified. Moreover, given the technical complexity of this device, the next step would consist in ascertaining its feasibility and testing it with some initial experiments.

Akbar, Arifa. 2021. "Rise of the robo-drama: Young Vic creates new play using artificial intelligence." theguardian.com. 24 August. Accessed June 23, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2021/aug/24/rise-of-the-robo-drama-young-vic-creates-new-play-using-artificial-intelligence.

Akten, Memo. 2021. Deep visual instruments: realtime continuous, meaningful human control over deep neural networks for creative expression. PhD thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London.

Artaud, Antonin. 1958. The Theatre and Its Double. Translated by Marie Caroline Richards. New York: Grove Press, Inc.

Befera, Luca, and Livio Bioglio. 2022. “Classifying Contemporary AI Applications in Intermedia Theatre: Overview and Analysis of Some Cases.” CREAI@AI*IA.

Di Bari, Francesca, et al. 2021. "A Journey of Theatrical Translation from Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels: From Fanny & Alexander's No Awkward Questions on Their Part to Story of a Friendship (Including an Interview with Chiara Lagani)." MLN 136 (1).

Epstein, Ziv et al. 2023. "Art and the science of generative AI: A deeper dive." https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.04141.

Hertzmann, Aaron. 2018. “Can Computers Create Art?” Arts 7 (2): 18.

Margiotta, Salvatore. 2020. "La pratica dell’eterodirezione nel teatro di Fanny & Alexander." Acting Archives Review X (20).

Offert, Fabian. 2019. “What Could an Artificial Intelligence Theater Be?” Fabian Offert's Blog. 12 April. Accessed June 23, 2023. https://zentralwerkstatt.org/blog/theater.

Rosa, Rudolf, et al. 2020. "THEaiTRE: Artificial intelligence to write a theatre play." arXiv preprint arXiv 2006.14668.

Sigman, Alexander. 2019. "Robot Opera: Bridging the Anthropocentric and the Mechanized Eccentric." Computer Music Journal 43 (1): 21–37.

Source: https://www.heinergoebbels.com/works/stifters-dinge/4 (accessed June 23rd, 2023)↩

Source: https://culture.pl/en/event/robots-perform-lems-prince-ferrix-and-princess-crystal (accessed June 23rd, 2023) ↩

Source: https://www.theaitre.com/ (accessed June 23rd, 2023) ↩

Source: https://marcodonnarumma.com/works/corpus-nil/ (accessed June 23rd, 2023) ↩

Source: https://research.rhizomatiks.com/s/works/discrete_figures/en/ (accessed June 23rd, 2023) ↩

Source: https://www.youngvic.org/whats-on/ai (accessed June 23rd, 2023) ↩

Source: https://improbotics.org/ (accessed June 23rd, 2023)↩

This essay employs necropolitical theory to investigate the imperative of late stage techno-imperialism to prevent its own collapse through establishing prototype warfare as a new model for military production. Research projects to develop Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) with Automatic Target Recognition (ATR) capabilities which have marked the initiation of prototype warfare will be examined to address the necropolitical notions of sovereignty embedded in the operational function of autonomous weapons as an extension of neoliberal state power. The central thesis of this essay aims to articulate the importance of positioning the critical role that IBM punch card technology played in automating the nazi holocaust as a core historical precedent for the production of autonomous weapons systems.

Prototype Warfare, Techno-Imperialism, Autonomous Weapons, Automation Technology, Necropolitics, Sovereignty, Execution

This essay will explore the emergent necro political terrain of late stage techno-imperialism, placing focus on aims set by the defense industry to apply rapid developments in automated weapons technologies to live combat scenarios on an experimental basis for the sake of optimizing capital accumulation in a practice known as prototype warfare. Techno-imperialism is conceptualized as the successor to techno-colonialism, which has dilated the scope of its extractive technologies to globally expand its reach of power. As techno-colonialism is predicated on the capitalist state having a severely asymmetrical concentration of control over technological production with which to exert hegemonic political dominance, it evolves into techno-imperialism as the profit gained from its extractive forces begins to stagnate or decline and thus requires new territories and modes of extraction to maintain the relevance and authority of this parasitic system. (McElroy, 2019) Technological research and development has historically been funded and directed by the military, with its operational functions driven towards the mandates of wartime production. (Edwards, 1997) Prototype warfare presents a novel phenomenon in this economic paradigm as it signifies a new era of warfare where the pursuit of capital to be gained through technological production has entirely superseded the political agendas underlying military invasion. Historically, preconceived ideological motivations, geopolitical conflicts and struggles for command over foreign resources preceded the development of new military technologies to be used as thoroughly considered strategic aids for the advancement of the neoliberal political program. The prototype paradigm evolves this dynamic as it centers technological innovation as the primary ideological motive propelling wartime operations as the profits to be gained from catalyzing advancements in the automation industry have become the next frontier of capitalist conquest. Through examining the ideological objectives and historical conditions that led to prototype warfare, I postulate that its onset indicates the decline of late stage techno-imperialism into crisis. This essay will commence by first examining the historical background of capitalism’s reliance on military technological development and the imperialist war industry for economic stability. The weaponization of IBM punch card technology by the Nazi regime will then be located as an important historical example of automation technology being made into a massively lucrative industry through its usage for mechanizing serialized execution. The essay then proceeds to further delineate the concept of prototype warfare and how it is currently being implemented by the U.S. Department of Defense(DoD). To conclude, I invoke Achille Mbembe’s theorization of necropolitics to consider whether the automation technologies historically used for exercising absolute power over the mortality of the population are evolving into new sovereign entities under the direction of prototype warfare. This provocation unfolds into a historical comparison between the necropolitical function of automation technology in the context of Nazi Germany and late stage techno-imperialism to argue that prototype warfare signals the inevitable decline of the capitalist system.

Capitalism routinely relies on technological and scientific advancement to further develop its productive forces. It is noted by Marx that when the advancing forces of science, technology and economic growth stagnate, revolutions occur as a means to remove the barriers inhibiting social progress. (Engels and Marx, 1932) World War II incited the introduction of new production techniques geared for purposes of war. Many technological innovations in aircraft manufacture, medicine, nuclear energy and telecommunications were born out of the realization of their value as a means of advancing wartime industry and military power. The military industrial complex continues to play a massive role in the development of global productive forces due to the state control leveraged towards funneling innovative research into projects focused on military initiatives (Gottheil, 1986). Global military spending totaled 1.981 trillion dollars in 2020 (Silva, Tian and Marksteiner 2021). Reich and Finkelhor (1970) posit that without militarism, the entire capitalist economy would return to the state of collapse it experienced prior to its rehabilitation by the second world war. Military production sustains the modern capitalist economy because its produced commodities are designed to fulfill the insatiable demands of war, which is waged relentlessly with no apparent end (1986).

Of the array of corporations that emerged from World War II having accrued billions in profit and expanded into global monopolies, IBM stands out due to the impact of an extensive business partnership held with the Nazi state. (Black, 2001) The Nazi's employment of automated information technology demonstrates its susceptibility to both adapt to and propagate a genocidal authoritarian agenda. Directives for advancing the functionality, processing power and data storage faculties of IBM’s calculation machinery were driven by the Third Reich's homicidal aim of identifying and destroying the lives of the Jewish people and those deemed undesirable to the fascist regime’s construction of an Aryan society. The programs curated by IBM personnel had to be designed to not only tabulate the personal information and assets of every individual in Germany, but to systematically map and sort citizen identities according to Nazi approximations of Jewishness, ethnicity, disability, neurodivergence, homosexuality and political disobedience. Data tabulations geared to extend the Nazi regime's war effort were orchestrated in a multi-tiered procedural apparatus in surveillant pursuit of tracking and coordinating the movement and location of every person, resource, livestock, artillery, ammunition, tank, vehicle, train and piece of currency in occupied German territory. (Black, 2001) The severity of the abuses inflicted by the regime's warmongering practices was accelerated by their fixation on optimizing the efficiency, order and systematization of the fascist political project through mechanization. Every stage of the Nazi’s operation was reliant on the equipment and technical expertise of IBM and the alarming expediency with which the holocaust was executed was due to the multi-territorial statistical analysis applied to the regimentation of the genocidal campaign through computation. Though guilty of profiteering off of the Nazi holocaust, IBM evaded culpability by way of the political protections offered to such a powerful corporation by the U.S. government. The spectrum of political and military advantages to be gained through IBM information technology lead to its adoption by the U.S. military for planning and conducting war strategies. (Black 2001)

The onset of the fourth industrial revolution, characterized as the next stage of the digital/information age has prompted a new revolution in military production dubbed “Prototype Warfare.” The concept of prototype warfare was developed in the 1990s and appropriates language found in complexity and information theory to articulate how the military can strategically yield technological advantage in the information age (Hoijtink 2022). Prototype warfare seeks to neglect the methodical mass production of well tested and refined ammunition, weaponry, and vehicles that reflected military industries of the past. Instead, prototype warfare proposes to use active battlegrounds and real-time operations as testing sites for the myriad of experimental, Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) enabled, military technologies being manufactured at small scales with unproven capabilities and functions. On par with the adoption of terminology from information theory, the military envisages a ‘decentralization’ of mass coordinated operations to effectively integrate the proliferation of A.I. enabled devices into a network that lacks a central point of weakness. Prototype warfare implies that battlefields are being situated as techno-scientific laboratories, platforms for the experimental interaction of A.I. assisted sensors, satellites, weapons systems, autonomous robots, unmanned vehicles and human life (Hoijtink 2022). Each of these actors will be poised as variables in risk intensive research practices that will necessitate an increased tolerance for failure by ground operation personnel. The impetus to forgo former standards of battlefield readiness and try out premature technologies on active battlefronts is largely driven by the mounting pressure that the international A.I. arms race has placed on the U.S. to outcompete political rivals China and Russia in its struggle to uphold technological supremacy and thus, political dominance on the global stage. (Sandels 2020)

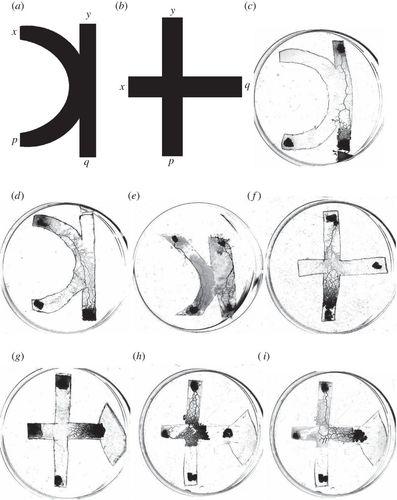

The concept of utilizing prototyping and experimentation practices within the domain of war was first declared as a central aim of the Department of Defense as part of the Third Offset Strategy initiated in 2014. The primary objectives of the Third Offset Strategy are to preserve U.S. military dominance within the field of A.I. and to further hone in on the research and development of robotics and system autonomy, miniaturization, big data, and advanced manufacturing through strengthening collaborative relationships between the U.S. military and innovative private sector enterprises. (Fiott 2016) Closely following the announcement of the Third Offset Strategy came the establishment of the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) in 2015 which seeks to accelerate the military's adoption of commercial technology and to rapidly prototype and field advanced commercial products that address national security challenges. The DIU was designed to evade rules and regulations customary of the defense acquisition process by leveraging the Other Transactions Authority in order to contract out prototypes in as few as 60 to 90 days. (Kuykendall, 2017) The launching of Project Maven in 2017, funded by the Algorithmic Warfare Cross Functional Team, was referred to by director Lieutenant General John Shanahan as the beginning of prototype warfare. In accord with the Third Offset Strategy’s goal to foster new and deeper relationships with the private sector, Project Maven sought the expertise and resources of Google in its quest to use A.I., deep learning, and computer vision algorithms to detect, classify and track objects within Full Motion Video Images. Though Google has ceased work on Project Maven since its contract with the Department of Defense (DoD) expired in 2019 due to mass resistance and backlash from employees, the project remains in operation under the control of the National-Geospatial Intelligence Agency. (Strout 2022) Project Maven embodies a robust vision for the use of A.I. in warfare, with further aims to extend the application of A.I. directed surveillance across many forms of data exploitation including Enemy Captured Material, Acoustical Intelligence, Overhead Persistent Infrared program and Public available information. The ultimate outcome of the project will be to outfit tactical UAVs with Automatic Target Recognition (ATR) capabilities, an effort which boasts the ability to reduce the kill chain decision making process from 20 minutes to 20 seconds by replacing human cognition with A.I. (Office of the Secretary Of Defense 2019). The overarching purpose of relegating the kill chain to A.I. enabled machine processes is to increase the efficiency of wartime operations by reducing the cost and time necessary for target identification and execution, and subsequently to increase lethality. Advances in automated weapons systems which are designed to maximize the death rates of those designated to be enemy combatants, simultaneously propel an increase in profit margins accrued by the arms industry, as defense contractors profit directly off of every bullet and missile fired.

In a paper titled Necropolitics, author Achille Mbembe lays a theoretical foundation for necropolitics/necropower as an expansion of Foucault’s conception of biopolitics/biopower which seeks to account for the contemporary methods of execution through which political bodies exercise sovereignty as a practice that is ideologically veiled in the operation of war. Mbembe’s construction of sovereignty disposes of its typical connotations with struggles for autonomy to focus on figures of sovereignty whose primary objective is the generalized instrumentalization of human existence and the material destruction of human bodies and populations. (Mbembe, 2003) This construction works to effectively define the sovereign figure as one who maintains the right to kill. When scaled to the level of state power, the right to kill is inflated into the authority to exercise control over the mortality of a population at large. The Nazi state is widely recognized as the epitome of biopolitical sovereignty due to a core function of its political operation being to organize the mass execution of the Jewish population.

Mbembe notes that it is argued by a number of analysts that the material premises of Nazi extermination are to be found in colonial imperialism on the one hand and in the serialization of the technical mechanisms for putting people to death on the other. Mbembe proceeds to reference how the gas chambers and ovens were the result of ongoing processes to dehumanize and industrialize death. He explains how through mechanization, serialized execution was transformed into a purely technical, impersonal, silent and rapid procedure. However, Mbembe does not discuss the tantamount role that the data tabulations performed by IBM punch card technology played in turning genocide into a mechanized process. (Mbembe 2003) The industrialization and mechanization of this genocide can only be explained by the methods through which punch card technology sorted through billions of bits of data representing the demographics of the entire population and systematically marked millions of individuals for death based on the Nazi’s classifications of who should live and who should die. Without punch card technology, the Nazi genocidal project would have arguably been of nominal scale if bound to the limitations of manual data processing. The Nazi regime’s historical positioning as the ultimate example of biopower is largely due to the efficacy with which they utilized automation technology as a hyperextension of sovereignty. I would further contend that the use of punch card machines to orchestrate genocide marks the earliest example of biopolitical sovereignty being outsourced to technology.

The production of UAVs equipped with A.I. enabled Automatic Target Recognition capabilities as a means of determining who is an adversary that will be killed by the state and who will be allowed to live distinctly echoes the employment of punch card technology as a tool for automating genocide. Autonomous weapons systems possess a historical parallel to the punch card machines designed for the Nazi state that is unmatched by other forms of technology engineered for war because they were both developed with the explicit goal of applying automation technology to the process of mapping a population into politically contrived classifications of who will live and who will die. Automatic Target Recognition acts as a contemporary reformulation of biopolitical sovereignty being hyperextended by and outsourced to technology. The development of A.I. programs designed for the purpose of determining who the state will kill provokes one to question if A.I. is being endowed with a novel form of biopolitical sovereignty and what this implies about the nature of the state it is being produced by. The introduction of prototype warfare as a method for revitalizing the military industry as a profitable extractive force signals that the viability of late-stage techno imperialism has reached a place of uncertainty. Late-stage techno imperialism now exists amidst a backdrop of burgeoning ecological catastrophe, growing social crises and heightening international political tensions. (Foster, 2019) The urgent need to accelerate military technological development through the reterritorialization of the battlefield as a laboratory for unstable autonomous weapons systems points to the global conditions which are pushing the dominance of an exploitation based socio-economic system to a place of greater instability. Positioning technological innovation as the driving motivation for military invasion serves as a prognosis for the threats that circumstances such as dwindling natural resources and the economic and military advancement of rival political powers pose to the dominance of western imperialism. In Marxist literature, Fascism is theorized as the transformation of a collapsing capitalist state into an authoritarian regime that aims to preserve the prevailing economic order by exacerbating the exploitation and persecution of marginalized groups and vastly expanding imperialist conquest as a source of financial gain. (Kawashima 2021) The conversion of Germany into the Nazi state exemplifies a liberal democracy that resorted to fascism as a means of fortifying the capitalist system when confronted with economic ruin. The Nazi state re-stabilized the failing German economy through dehumanizing the Jewish population into an extractive resource and establishing a military industry that was fueled by the destruction of human life. Contemporary Marxists speculate that late-stage imperialism will turn to neo-fascist tendencies in response to the decline of its extractive forces. (Foster, 2019) Prototype warfare seeks to create a profitable framework for autonomous weapon production by reconfiguring military invasion into a perpetual technological experiment which renders human life into an extractive resource.

Black, Edwin. 2001. IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation.

Engels, Friedrich and Karl Marx. 1932. The German Ideology. The Marx-Engels Institute.

Edwards, Paul. 1997. The Closed World: Computers and the Politics of Discourse in Cold War America. The MIT Press.

Finkelhor, David and Michael Reich. 1970. Capitalism and the Military Industrial Complex: The Obstacles to Conversion. Review of Radical Political Economics. 2:4.

Fiott, Daniel. 2016. Europe and the Pentagon’s Third Offset Strategy.The RUSI Journal, 161:1, 26-31.

Foster, John Bellamy. 2019. Late Imperialism. Monthly Review, 71:3.

Gottheil, M. Fred. 1986. Marx versus Marxists on the Role of Military Production in Capitalist Economies. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 8:4, 563-573.

Hoijtink, Marijn. 2022. “Prototype Warfare”: Innovation, Optimisation, and the Experimental Way of Warfare. European Journal of International Security 7, no. 3, 322–36.

Kawashima, Ken. 2021. Fascism is a Reaction to Capitalist Crisis in the Stage of Imperialism: A Response to Ugo Palheta. Historical Materialism.

Kuykendall, Roger. 2017. Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIUX): Innovative or Excessive?. Air War College, Air University.

Office of the Secretary Of Defense. 2019. PE 0307588D8Z: Algorithmic Warfare Cross Functional Team, Budget Item Justification. Unclassified Document. https://www.dacis.com/budget/budget_pdf/FY20/RDTE/D/0307588D8Z_189.pdf

Marksteiner, Tian, and Dr. Diego Lopes da Silva. 2021. Trends in Global Military Expenditure, 2020. SRPRI.

Mbembe, Achille. 2003. Necropolitics. Public Culture, Volume 15, Number 1, Winter 2003, pp 11-40, Duke University Press.

McElroy, Erin. 2019. Data, dispossession and Facebook: techno-imperialism and toponymy in gentrifying San Francisco. Urban Geography, 40:6, 826-845.

Sandals, Carlos Miguel Branco. 2020. The beginning of Artificial Intelligence arms race: A China-U.S.A. Security dilemma case study. Universidade de Évora, http://hdl.handle.net/10174/28613.

Strout, Nathan. 2022. Intelligence agency takes over Project Maven, the Pentagon’s signature A.I. scheme. C4ISRNET, Intel/GEOINT.

How do bodies incorporate networked technologies in their sexual experiences? F*cking with the virtual looks at “cybersex” from the 90s and early 00s to discuss how it has materialized through contemporary commercial sexual technologies: interactive sex toys, VR porn, and dating apps. Using a lens of affect theory, the three cybersex technologies at the center of the essay indicate a move in modes of interfacing: from the visual/textual to the immersive and finally to the interactive experience. In the early 2000s, cybersex was imagined as an immersive and mediated sexual experience facilitated by technological gadgets and wires. Those technologies have influenced cybersex technologies and their design today. This paper offers a brief survey of the history of cybersex technology, considering how to use affect theory and modes of interfacing to consider what cybersex can tell us about our past, present, and future intimate relations to technologies.

Cybersex, Technology, Embodiment, Desire, Sexuality, VR Porn, Teledildonics.

What role do the body, embodiment, and sensation play when we have sex online? This paper explores instances where “cybersex,” as imagined in the 90s and early 00s, has materialized in contemporary commercial sexual technologies: interactive sex toys, VR porn, and dating apps. The three cybersex technologies indicate a move from the visual/textual (sexting) to the immersive (VR porn) and finally to the interactive (teledildonics), tracing not only the changes in the cybersex experience but also how contemporary technologies are directly influenced by techno imaginations of the past.

While, terms like affect, the body, cybersex, and the virtual have become slippery surfaces in theoretical encounters. I define cybersex as sex with and through technology, an erotic encounter that utilizes some form of technology to occur. I define affect,as sensation, an intensity experienced by both body and mind together following a Spinozist legacy, introduced by Gilles Deleuze and elaborated further by Brian Massumi and by critical studies during what Patricia Clough defines as the “affective turn” (Clough 2007, 1). It is crucial to think of the virtual as it relates to technology, cyberspaces, and VR/AR technologies through a lens of affect in an attempt to bring embodiment back into the technologically mediated landscape.

Intensity, sensation, and vibration become central in this approach as they allow sensation and affect to circulate between technologies and bodies, human and non-human agents.Expanding on this idea, affect is experienced on the body and through the senses; it is a visceral experience where mind and body are interrelated unity. Affect is a force, intensity, or flow that penetrates the body and increases or decreases its power and capacity to act. (Spinoza 2005, 70). Affect can be a valuable theoretical tool when considering cybersex because it can account for this centrality of sensation and the multiple transformations of desire, lust, stimulation, and vibration that moves between bodies and technologies.

In cybersex encounters, the human body appears entangled with different technologies to reach outward and extend, seeking another body, skin, vibration, message, or encounter. Thus, the body meets first with different technologies and each of them carries its own mode of interfacing. The interface or mode of cybersex shapes the experience of cybersex. For Alexander Galloway, interfaces can be screens, windows, keyboards, sockets, holes, or channels. It is only when they are in effect that interfaces can materialize and reveal what they are. In this way, Galloway defines as “the interface effect” the process of mediating thresholds of self and world (viii). The mode of interfacing between the screen/body determines how mediation operates and affects the online experience. How do we interface with technologies to connect intimately with each other?

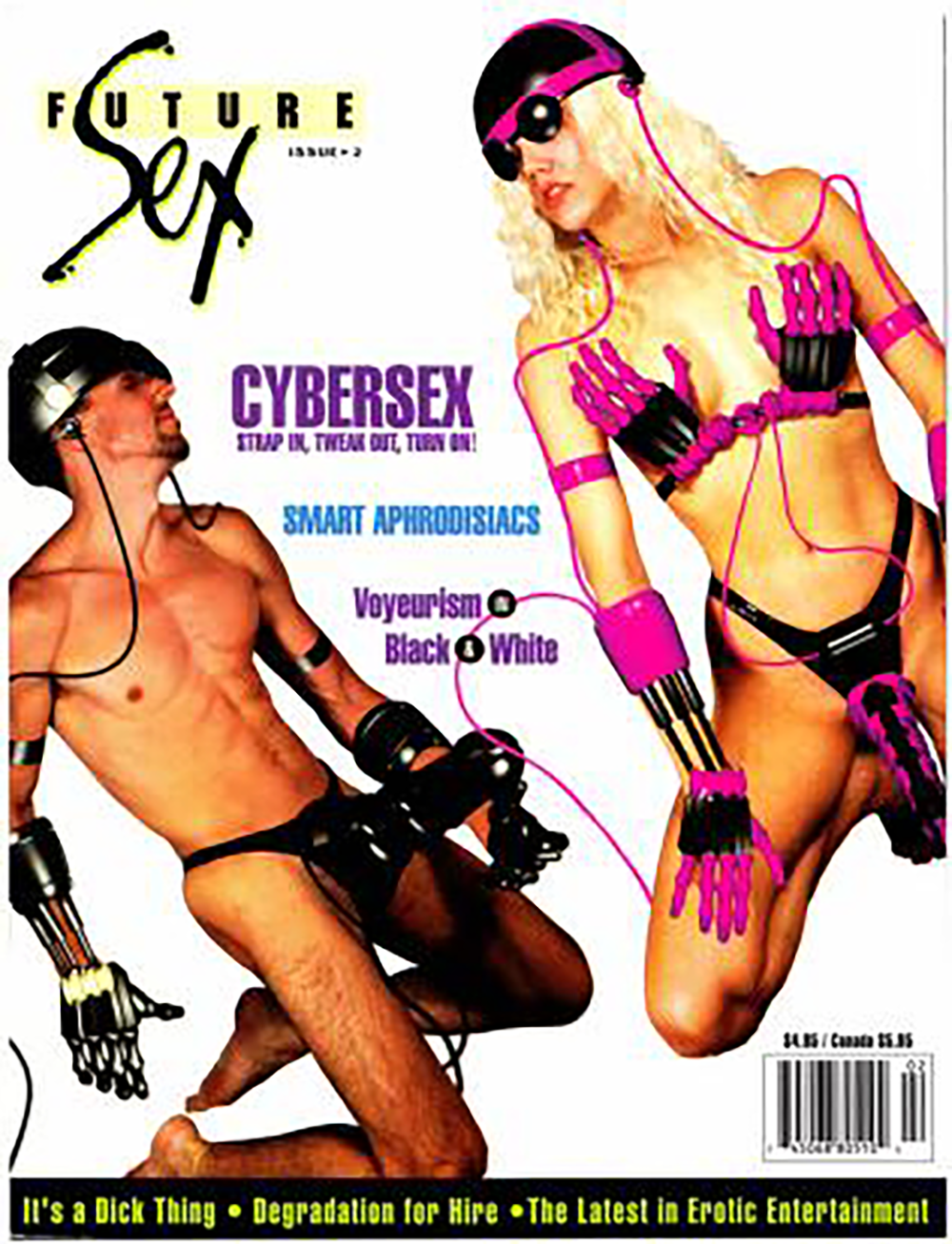

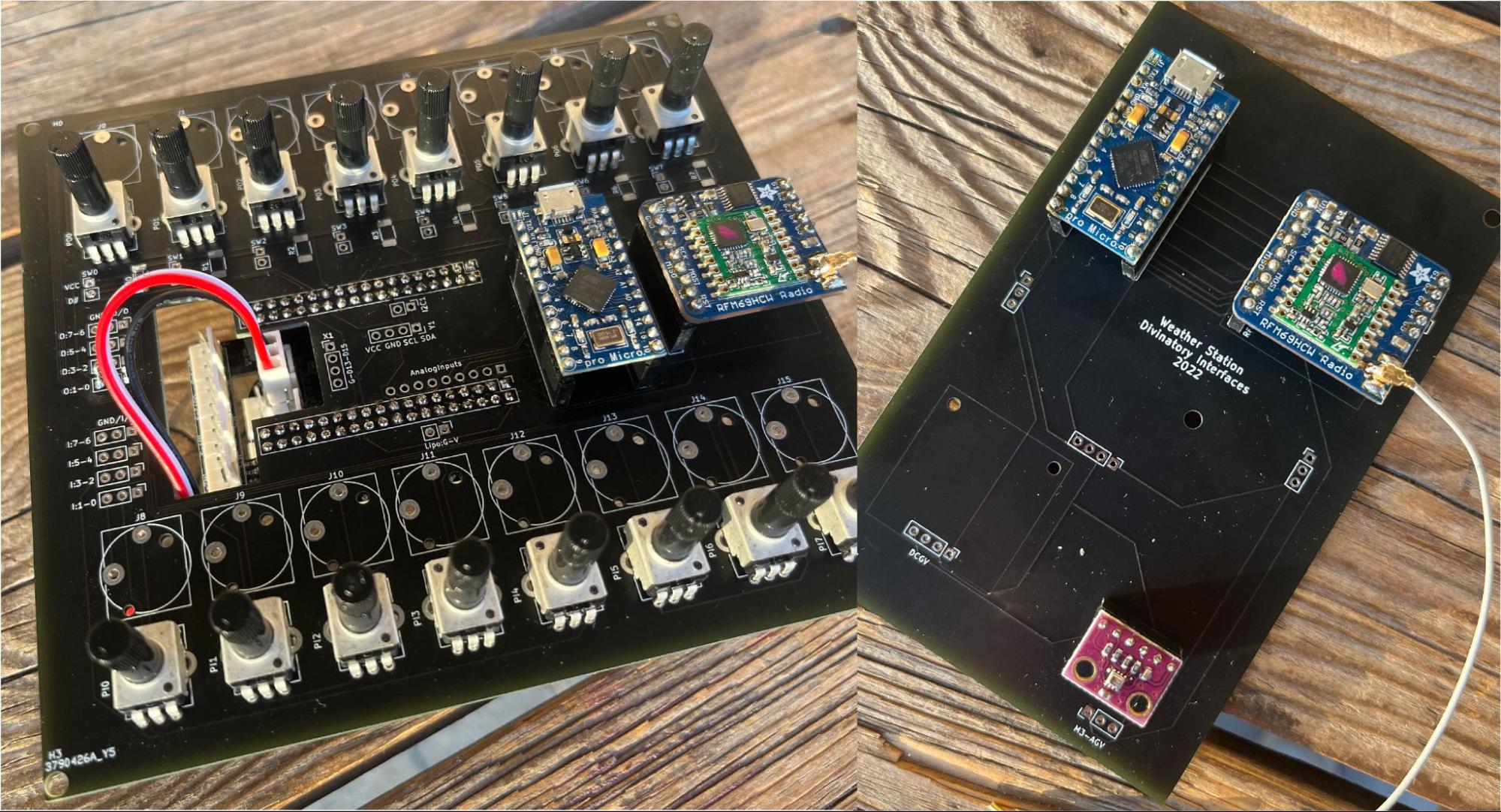

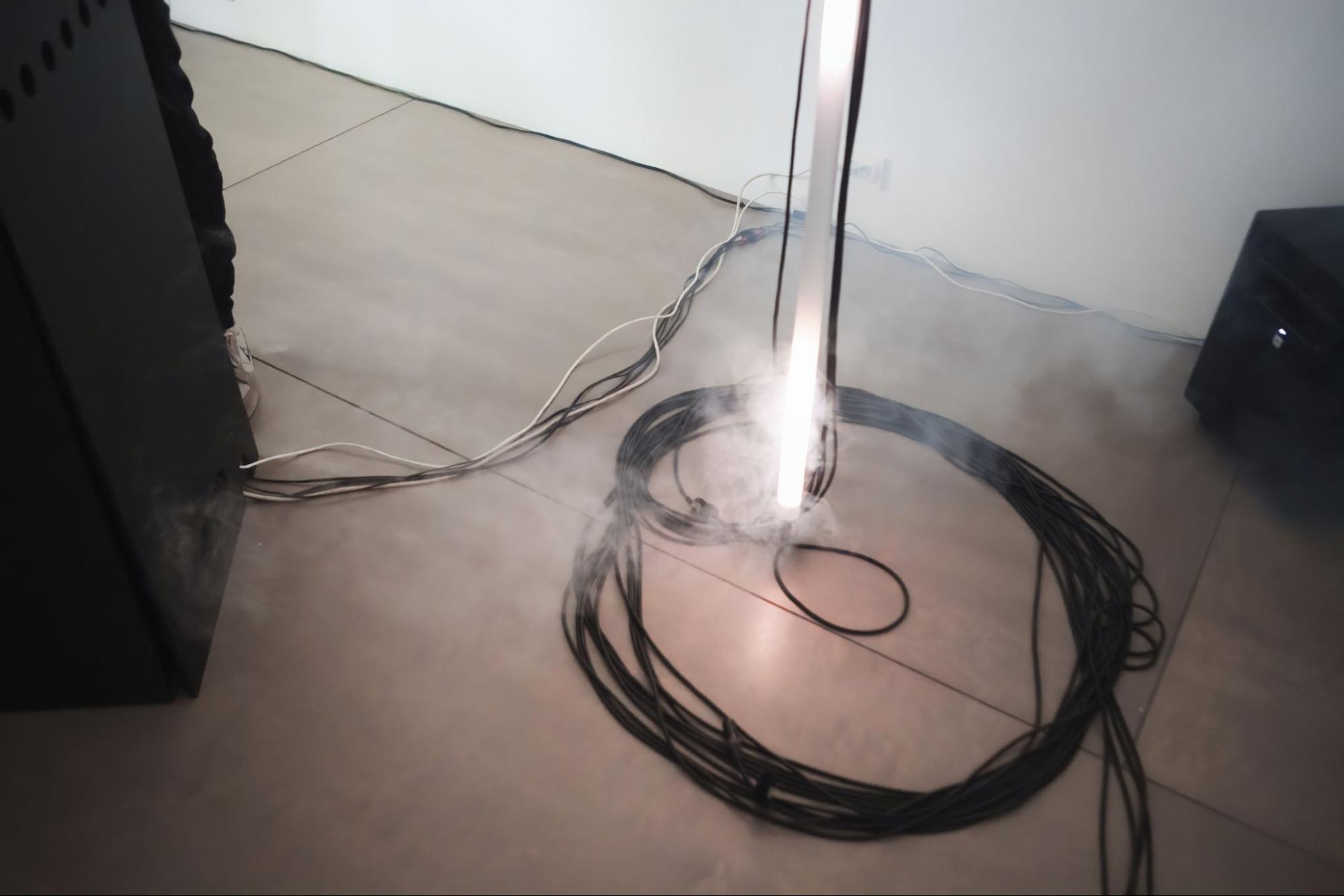

In the earlier techno-imaginaries of cybersex (fig.1), all modes of interfacing work in tandem and coexist to create a united experience, an immersive illusion of interactivity. Today, they have materialized not only as distinct technologies but as distinct modes of cybersex. Cybersexual interaction has moved from textual and audio communication to visual and audiovisual, to the promise of the immersive allowed in VR porn, to arrive into today's wireless interactive Bluetooth-enabled sex toys. The relationship between the body and the interface technology (whether a laptop, phone, VR headset, sex toy, or both) creates a bodily relationship in physical space.

The interface determines the rules of the interaction; it defines the affordances and the allowances of the communication, and how users relate to both the “experience” and the “screen.” In The Posthuman, Rosi Braidotti explores how the relationship between human bodies and technological others moves between intimacy and intrusion (Braidotti 2013, 89). Braidotti’s notion of “becoming machine” sees bodies and machines as intimately connected through simulation and mutual modification within a circuit of representation-simulation–biomediated bodies. The different modes of interfacing in cybersex structure cybersexual assemblages where affect transforms and reshapes itself as it moves between human and non human organs, cables, code, wireless connections, and more.

Following Braidotti’s ideas, a focus on the technologies of cybersex and how they come to touch with the human body allows us to move from disembodied cyberspace into an embodied sensorium where the body becomes the center of the experience. Cybersex crafts a unique setup where the body becomes vulnerable in front or next to technology while also disguised behind a nickname, a profile or VPN address. Still, there is a tenderness and a vulnerability the technology that controls and determines the modality and shape of our interaction.

To think of the body in cybersex, we first have to think of the body in cyberspace and Virtual Reality(VR). Who is the subject that is fucking with the virtual; sits in front of the computer; holds the smartphone swiping and sexting; takes nudes standing in front of a mirror; wears the VR headset to be immersed in a sexual, mystical journey in cyberspace; connects via Bluetooth connected sex toy to a lover far away. The mediated landscape of being online, and the technological tools that one engages with to access “cyberspace” have been completely transformed with the emergence of new technologies. Thus, our contemporary online spatial experiences and communities might not be similar to the cyberspace imagined in science fiction.

In The War of Desire and Technology in the Close of the Mechanical Age, Sandy Stone (1995) sees cyberspace as a social environment, one that allows interactions not only between people but also between humans and machines. Those interactions between humans and machines and humans to humans through the machine, allow a new identity to emerge. For Stone, cyberspace is “a space of pure communication, the free market of symbolic exchange–and as it soon developed, of exotic sensuality mediated by exotic technology.” (Stone 1995, 33)

In the 1990s, magazines like Mondo 2000 (1984-1998) and Future Sex (1992-1994) emerged as an intersection of cyberculture and sexual positivity influenced by cyberpunk fiction writers like William Gibson and Bruce Sterling. In their pages, cybersex was imagined as the future of sex, a combination of sex, drugs (mainly LSD), and future technology that create an enhancing simulation. A prevalent issue when thinking of cybersex in films, magazines, and cyberpunk discourse was how the sensations experienced by the virtual body in cyberspace could be felt on the physical body of the participant. Solutions come in many forms: Howard Rheingold imagines teledildonics (1992, 345), Kroker imagines electric flesh (1993), and films like “The Lawnmower Man” (1992), “Brainstorm”(1983), and “Live Virgin” (2000) envision cabled bodysuits, machines, and architectures that engulf the body so that they can mediate sensations from the cyberspace to the body that stands with/in or on the side of the device to experience cybersex.

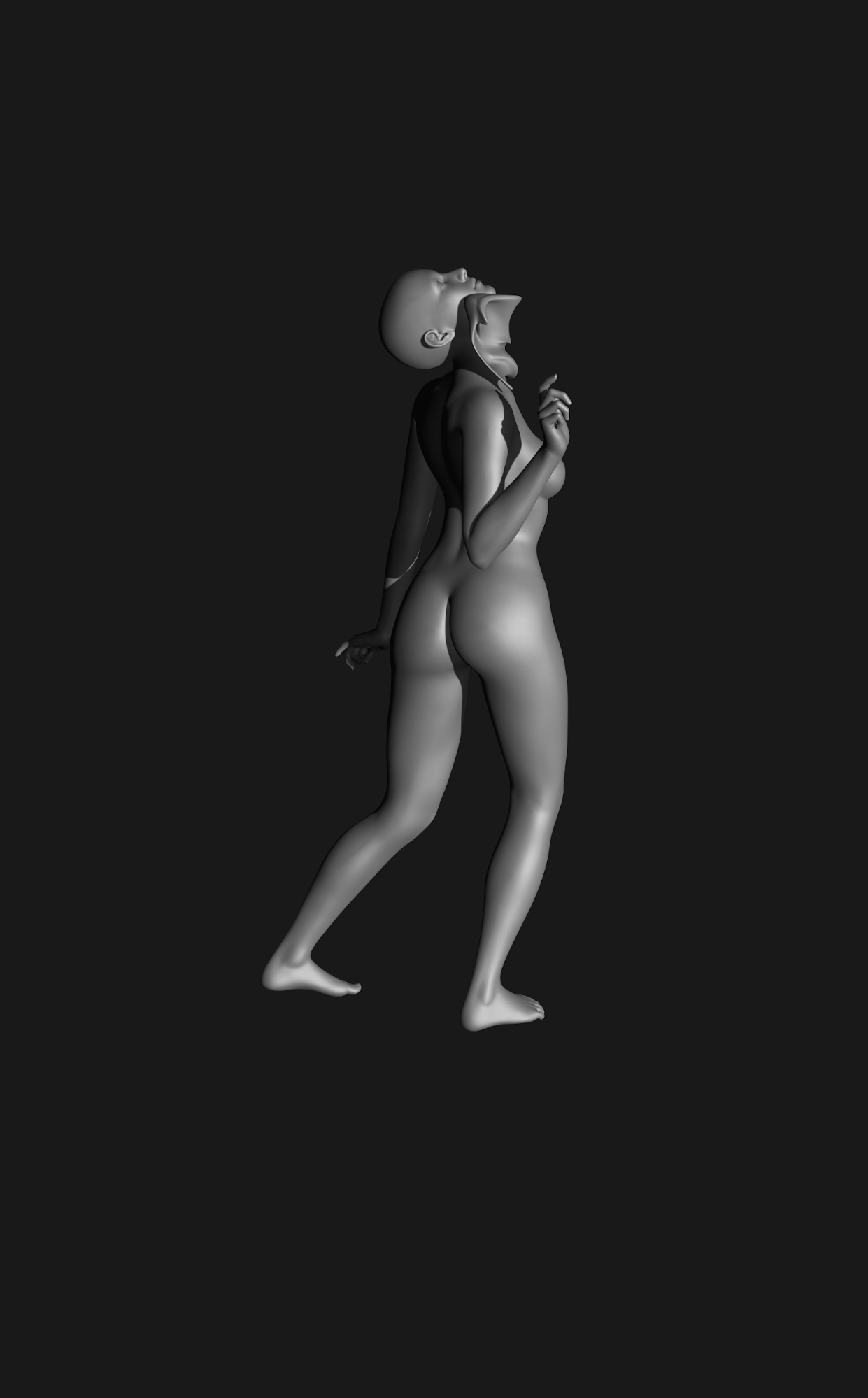

In 1992, on the cover page of the second issue of the magazine Future Sex, we see two naked bodies, male and female, enhanced with different technological gadgets and wires: thongs with strap-ons, arms replaced with robotic arm suits, a wired helmet, and goggles connected with wires. Following the magazine's headline “Strap in, Tweak out, Turn On!” the two models are enhanced with technology to experience “Cybersex 2.” Michael Saenz and Reactor speculate how fabrics, sensors, immersive 3D technology, and tactile data would create erotic simulations without the dangers of human interaction (Saenz 1992, 28). The lovers' encounter occurs in cyberspace; the Virtual Reality headset offers access to cyberspace; the sensations experienced during cybersex are felt on the body through teledildonics and bodysuits. In this image, cybersex is imagined as an immersive and mediated sexual experience facilitated by various devices. This early image of cybersex highlights the centrality of the body and how it interfaces with sensory network technologies. The body becomes a mediator; the technologies allow the body to feel through sensory stimulation, an encounter in virtual cyberspace. Furthermore, it is the technologies depicted in this techno-imagination that are now thirty years later defining the future-present of sexual technologies. How have those fantasies of cybersex been realized today through specific technologies?

The simplest modality of cybersex is fostered as peer-to-peer interaction that takes place using text, sound, or images. From the phone to the computer to the smartphone, from the AOL chatroom to Second Life, cybersex seems to be experienced in writing (textual), in voice (auditory), in the image (through an exchange of images and or representational sexual acts within videogame). Technology acts as a mediator and interface between the two desiring subjects. The technology stands in-between them, creating an excitement of participating in a subculture that is dark, exciting, forward, and futuristic.

In “Romancing the Anti-Body: Lusting and Longing in (Cyber)space,” Lynn Hershman Leeson discusses how by default, cyberspace requests the user to create a mask, structuring a computer-mediated identity that might correspond or not correspond to reality. For Leeson, as users are asked to redefine themselves through names, profiles, icons or masks they are also determining their audiences spaces and territory. In this way “anatomy can reconstituted.” (Hershman-Leeson 1996, 325)

Research on cybersex often discuss the potentialities of assuming avatar anti-bodies online, well-crafted personalities that allow for each physical body standing in front of the computer to have multiple corresponding bodies in cyberspace. Users in Compu-Serves having compu-sex, users behind phones having phone sex, and users of Second Life, using their avatars to have cyber sex, share some similar experiences. Those experiences share the element of crafting new identities and creating desire-ing and desirable bodies. In the environment of the contemporary dating app, texting and exchanging images become a central element of communication. This time the smartphone touch screen becomes the central interface with which the body engages. This text and image-based sexual communication seem almost like a descendant of the anonymous space of the chatroom that proliferated in the early 00s.

In Virtual Reality , Howard Rheingold (1990) imagines virtual reality sex as a collaboration between virtual reality and teledildonics. Rheingold imagines that through the marriage of virtual reality and telecommunications networks, teledildonics would allow sexual stimulation to occur by reaching out and touching other bodies in cyberspace. By incorporating a lightweight bodysuit and 3D glasses (VR headset) one could have a realistic sense of visual, auditory and haptic presence (346), what Rheingold calls an “interactive tactile telepresence” (348). Contemporary VR porn utilizing a VR heaset and a stroker pairing the porn strokes to the toy through AI, is the closest thing we have to this immersive vision of cyber sex.

In the Foreword of Hard Core, Linda Williams (1989) positions pornography as a genre that moves the viewer's body in a particular way. Contemporary VR porn creates a spectacle of visual pleasure where the contemporary stroker allows the viewer's body to be moved in the rhythm of porn, making any VR porn experience interactive. The headset enables immersion, and the stroker promises that the immersion is not only felt on the body but is perfectly paired with what you are viewing: the flow of the porn is the flow of the stroker. VR porn technology promises you can “Feel what you see” in real-time.

At the same time, VR porn structures a particular form of gaze, an embodied male gaze. There are two ways of looking in VR porn. In solo films and girl-on-girl films, the camera is placed at a safe but close distance to the spectacle, creating a rather voyeuristic gaze of someone who is there looking at the scene from nearby. The 360 camera creates a fishbowl effect; at the center of the scene lies the action/spectacle of the female pornstar(s) who is the center of attention. Mainstream VR porn films place the viewer in the center of the action as an active participant embedded in the body of the male pornstar in the scene.

What is striking in mainstream VR porn is how the gaze is pinned on the body of the male performer, who wears the 360 camera. There is a body that limits the gaze. The particularities of this body dictate the gaze, how it is elevated, and how to participate in the scene. The hands of the male pornstar mainly stay on the side, only rarely participating in the sexual act. The phallus of the male pornstar becomes the interactive element, the point of touch between the spectacle and the immersion, as this body part gets stimulated by the stroker.

Beyond the immersive experience of VR porn, teledildonics today are also marketed toward couples in long-distance relationships. Bluetooth wireless remote control sex toys for couples in long-distance exemplify the concept of virtual sex, allowing couples to “feel each other” when they are apart. In advertisements and representations, Bluetooth sex toys are often advertised as a stand-in or proxy for a partner in a long-distance relationship. In the companies’ narratives, wireless sex toys can replace sexual experiences with a video call and a pair of interactive sex toys. Bluetooth sex toys are both toys but also a complex technology that allows affect, desire, and data to circulate.

Cybersex using interactive sex toys facilitates encounters between human and non-human sexual organs, wireless and Bluetooth connections, smartphones, screens, and satellites. The promise of sex across distances is enabled by the virtual but only through digital technologies: smartphones, Bluetooth-connected sex toys, modems, and more. In "Technology and Affect: Towards a Theory of Inorganically Organized Objects,” James Ash defines inorganically organized affect :

an affect that has been brought into being, shaped, or transmitted by an object that has been constructed by humans for some purpose or another (Ash 2015, 87).

Ash argues that there should not be an ontological distinction between organically and inorganically organized types of affect. Still, it is necessary to understand how affect travels and changes from matter to matter, from objects to waves to humans. At the end of the article, Ash nods towards how an object-centered account of affect can decentralize the human to think about affective design, objects, encounters, and their afterlives. This expansive theorizing of affect can allow us to better consider this relationship between bodies and machines in cybersex. Bluetooth sex toys viewed through a lens of affect and intra-action can allow us to think about how we embody and relate to technology to argue for the need to consider intimate affective assemblages constituted by humans and technological others or non-humans.

Our technologies have been completely transformed, but our futuristic cybersex fantasies look the same. As bodies interface habitually with devices that connect to the internet and store data in the cloud, our ideas of cybersex remain connected to their historical precedents. It becomes urgent, to explore the imaginations of the past next to the representations of the present to consider this concept of feeling the virtual or sensing the other, connecting intimately through technology to feel each other.

I would like to thank the Keneth Cordray GROW Summer Dissertation Fund, the Arts Dean's Fund For Excellence and Equity scholarship, and the UCSC, Film and Digital Media Department Summer Research Award for making my participation in the School of X possible.

Ash, James. 2015. ‘Technology and Affect: Towards a Theory of Inorganically Organised Objects’. Emotion, Space and Society 14 (February): 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2013.12.017.

Braidotti, Rosi. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambrdige, UK; Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Clough, Patricia Ticineto. 2007. ‘Introduction’. In The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social, edited by Patricia Ticineto Clough and Jean Halley, 1–34. London; Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Galloway, Alexander R. 2012. The Interface Effect.Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA: Polity.

Kroker, Arthur. 1993. Spasm: Virtual Reality, Android Music and Electric Flesh. Edited by Bruce Sterling. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Hershman-Leeson, Lynn. 1996. Clicking in: Hot Links to a Digital Culture. Seattle: Bay Press.

Mondo 2000. 1989. Mondo 2000 - Issue 01 (AKA Reality Hackers Issue 07). The Internet Archive. Accessed May 2023: http://archive.org/details/Mondo.2000.Issue.01.1989.

Saenz, Mike. 1992. ‘The Cybersex 2 System’. Future Sex-Issue 02.. Kundalini Publishing. The Internet Archive. Accessed on May 2023: https://archive.org/details/Future.Sex.Issue.02

Stone, Allucquère Rosanne. 1995. The War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the Mechanical Age. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press.

Rheingold, Howard. 1992. Virtual Reality: The Revolutionary Technology of Computer-Generated Artificial Worlds - and How It Promises to Transform Society. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Spinoza, Benedict De. 2005. Ethics. Edited and translated by Edwin Curley. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin Books.

Williams, Linda. 1989. Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the Frenzy of the Visible. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

This paper is an introduction to an ongoing transmedia art project. This project will address Machine Learning as an artistic medium. This paper will provide a quick overview of what the project aims at talking about, and why I chose to do it the way it does, before more precisely dwelling on the question of the Machine Learning’s ontology, mobilizing mainly the insights of Brian Cantwell Smith, a computer scientist and philosopher, and Jacques Derrida.

Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, AI Art, Counterfactual fictions, Avant-gardes

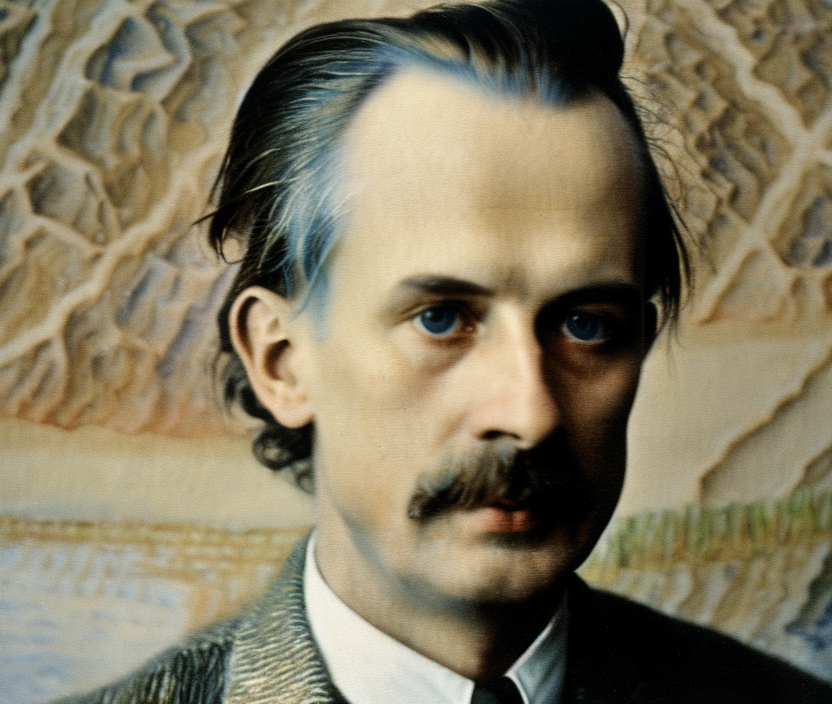

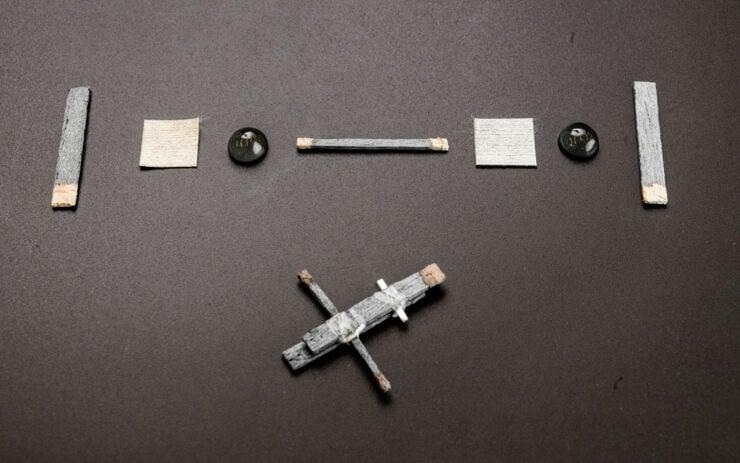

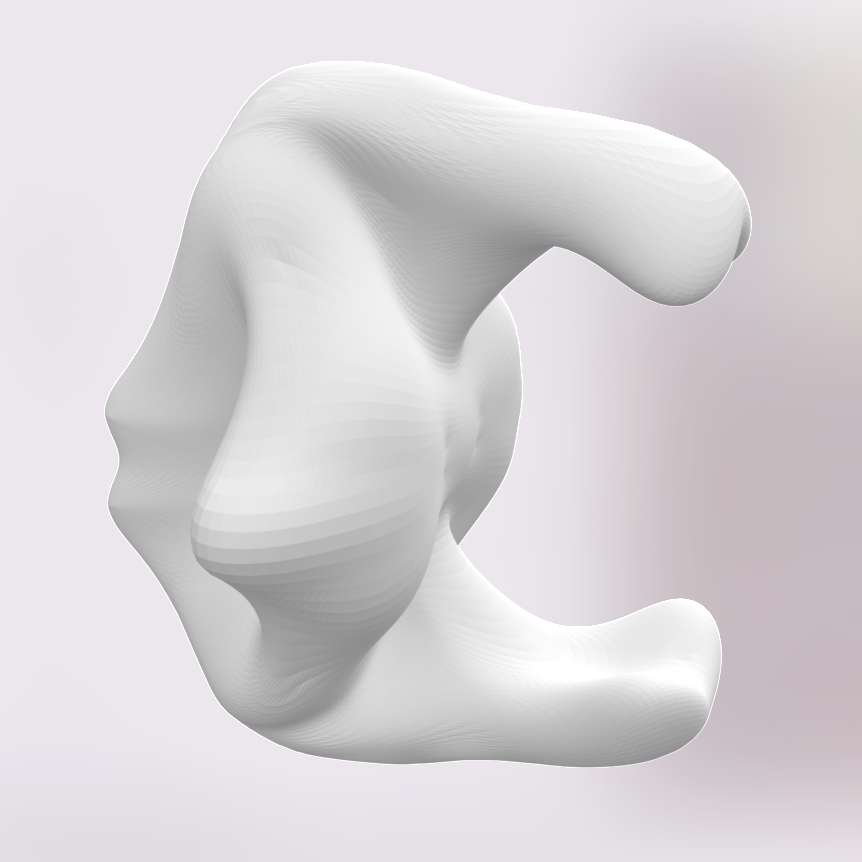

Melodia Atomizacji is an ongoing artistic project comprising a series of installations and an artist book. Both sides of this project intend to immerse the audience in the work and life of Sena Plincski, a Polish artist from the early twentieth century. Soon enough, though, one might realize that all of Sena’s paintings are presented through a series of strangely similar photographs, or that some of the people he wrote letters to were born twenty years after his disappearance.

This might have to do with the fact that Sena Plincski is entirely fictitious. I created this character, gave him a biography and a corpus of artworks, enmeshing him in a web of references that define his life and production as a negative of other, historically real, people. Sena is a fiction used as a front to explore, from a hands-on perspective, the techniques of Machine Learning (ML). More specifically, as will be addressed in this paper, this project is a take on what Brian Cantwell Smith refers to as ML’s ontology:1 i.e, what kind of representation of the world and its inhabitants is mobilized in these technologies. I will also provide some diegetic elements about Sena Plincski as context, as well as a brief explanation of why I decided to use such a narrative tool.

Because of its use of fiction, Melodia Atomizacji is ever-more layered. At the foundational level, there is me, an artist willing to experiment with AI image generation. Immediately piling up, is a need (its reasons being explained in the next part of this paper) for a figurehead that would embody ML functioning through his aesthetics preferences. But then, another layer is added, because not only does this figurehead need to have a corpus that visually reflects what is investigated, it also needs a biography; or, more precisely, a lore. In video-games, a lore is defined by contrast with the main narrative. It is all the world-building asides: all ancillary and accessory elements accessible through, for example, environmental storytelling or object descriptions.2 Here, I choose this term over biography because Sena does not have a life in itself. He exists through his connection, his fictitious symmetry, with other people’s works and lives. Even his whereabouts, and the time period during which he lives, serve as metaphorical clues about, first, his non-reality, and second, how and why I came to construct him as he is.

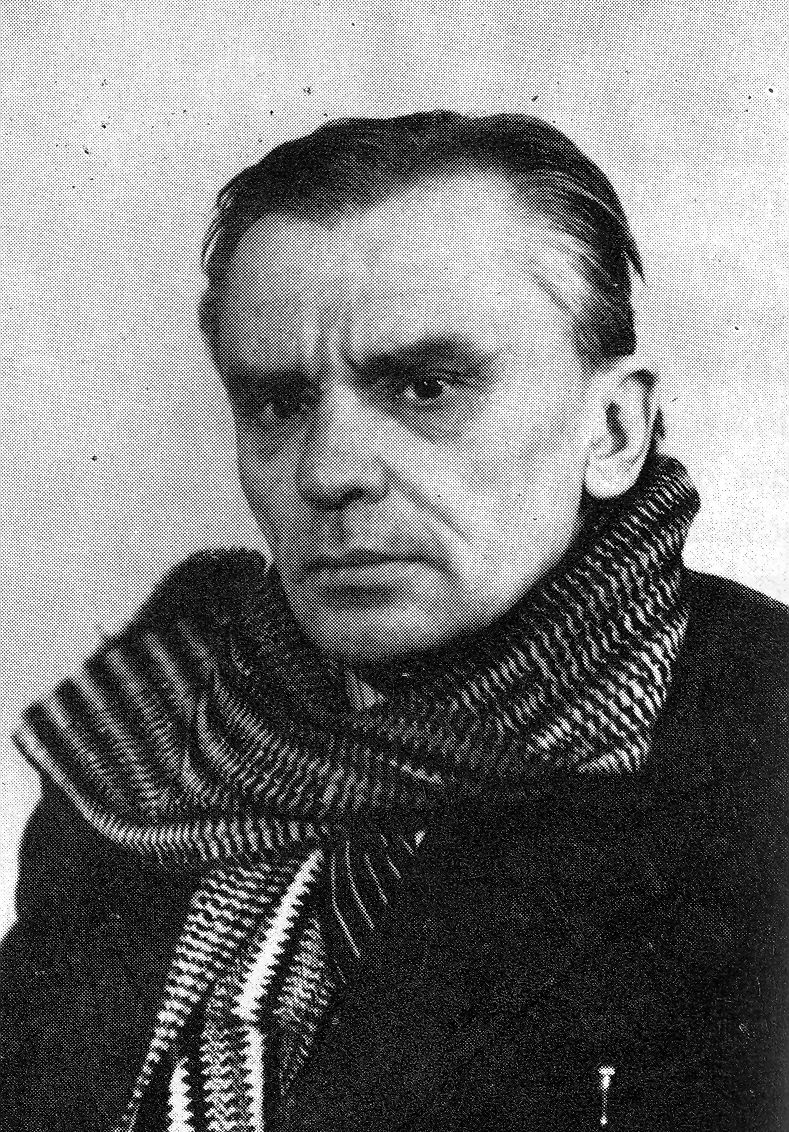

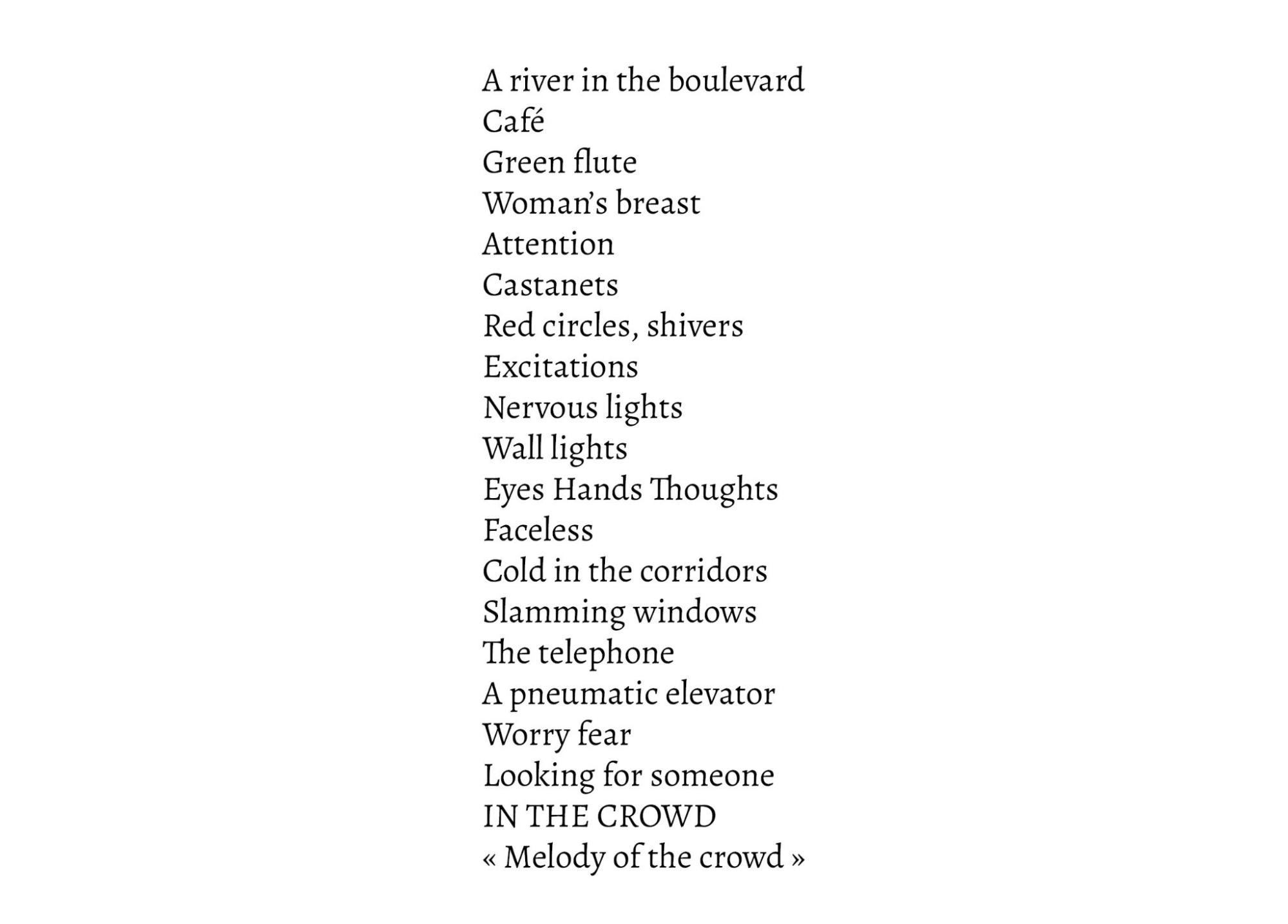

In this regard, I stay indebted to Maria Delaperrière, for her article on polish poetry and its relationship with the French avant-gardes of the early twentieth century3. It is in her paper that I learned about Tytus Czyzewski, one of the most well-known figures of the Formis’ci (Formist) movement. A painter and a poet, Czyzewski notably published a book called Zielone oko (Green Eye), that contains the poem Melodia Tlumu (Melody of the Crowd). This poem is one of the defining elements of this project because it reads like a proto-Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, by Georges Perec,4 a text where the writer lists everything he is seeing, in an apparently disconnected fashion, until the words start to lose meaning and their written form becomes the material itself.

But what interested me even more is the fact that Czyzewski, later on, said that his goal wasn’t to devoid the words from their meaning. It was quite the opposite, as a way to show how he, a polish exile in a foreign country, tried to connect to this place but kept getting devolved by all of what he was listing: the sound of the streets, the sight of the people passing by, etc. Opposing, then, the ML tendency that Sena is to embody, to treat any cultural or meaningful content as statistical probabilities, without regard for their meaning.

So Sena began as an anti-Czyzewski, then I decided he would go on to live in California, first Los Angeles and then what would become Silicon Valley, dabbling into occultist circles and making a reputation for himself by forging fake medieval engravings – which adds another layer to the project, with Sena creating fictions inside his own fiction – and opposing Aleister Crowley upon questions of decency. That’s where he would live until his disappearance on July 7, 1930, giving us access to all the letters he ever wrote in his life but never sent to the people they were destined to.

Stepping out and aside from the fiction, I’d like to briefly give a few reasons why this project came to be as it is now. This project started in 2022, as I entered a program centered on “Artificial Imaginations” – a play on Artificial Intelligence – directed by Gregory Chatonsky and Yves Citton. As we started experimenting with Dall-e or Stable Diffusion, I grew frustrated. These text-to-image tools seemed to put me in too much of a directing position: describing what I would like to see to the machine that would produce something I had to deem close enough or not. As an artist, I tend to – and aim at – working with systems. Webs of information and references set in motion by protocols and scripts. What interests me, in focusing on digital computational tools, is their ability to overwhelm me in their complexity and outputting ability. Because I can no longer predict what will be outputted, yet I conserve some leverage over the program, the piece comes to be constructed by the system itself as much as by me. Focusing on serendipity and iteration through a computational back-and-forth. The playground of Dall-E offered me the exact opposite of a praxis, which, to sum it up, meant that I couldn’t care less about the images produced.

Yet, I still found exciting the counterfactual potential of these technologies; that they were very promising fictitious archives providers. Hence came the desire for an encompassing fiction, something that would take a third seat between the AI and me. Something I could make these images interact with, as a way to go beyond this binary evaluation of “This is/isn’t what I want to see”.

The second reason, once I decided to go through the extra steps of building a character and giving it a biography, is that fiction is well-suited to both a) a transmedia narrative, and b) a fragmented form. It organizes what can seem disparate, instrumentalizes the various materials within a regulatory framework. Which plays well with one of my main stylistic inspirations : the creepypastas.

Creepypastas are short stories narratively lacking. These fictions, typical of post-internet writing, are woven in the absence of information around scattered elements, often presented as if found, and require a participatory reading. This particular format allows me to both extend my project across several media, but also to work on blurring the boundary between archive and creation, playing with the counterfactual potential I just mentioned. As for the fragmented form, it means to me that every element of the piece, every bit of image, installation, objects, and so on, doesn’t have to carry the whole meaning of the piece by itself, that it is the fiction, inserted in the space between each and every bit of visual, that is responsible for building the overall point. The fiction of Sena serves as the between-the-images.5

Lastly, the fiction that is Sena Plincski, his dipping into occultism and fight against meaning, allows me to shift the framing of this project away from what would be expected. My intuition being, paraphrasing Simon Penny, that we are now so much engrained with digital technologies, that they constitute the very images we use when talking about them.6 So, it is my firm belief that, in an artistic context, the investigation of such technologies is helped by reframing them out of their ordinary context. And, to this end, I found that the formist movement of the early twentieth century in Cracow, as well as the Hollywood-occultist craze of the Roaring Twenties, is quite a radical displacement.

Finally, regarding this question of ML’s ontology, as it will be addressed in this project. The crux of my argumentation lies in the opposition between the previous attempts at AI (What John Haugeland nicknamed Good Old Fashioned AI, GOFAI)7 and contemporary ML-based AI. Historically, in a Cartesian infused-vision of what it means to be intelligent, a lot of the effort was directed towards reasoning upon “clear and distinct entities, exhibiting defining properties and specific behaviors”.8 In response to the failure of this approach, ML was built upon not trying to represent (as in constructing a formal definition of) what it is working upon. More precisely, it uses statistical induction of proximity probabilities, encoding these statistical probabilities as weights in the connection of small and simpler calculating units; and, it needs to be noted, by removing any semantic value to these connections. Meaning that the machine itself does not know, can’t know and must not know what it is working. As a paradoxical example, facial recognition became frighteningly effective when scientists stopped trying to explain what constitutes a face and what is identity-confirming of a specific face next to another. Explaining it would require to build a formal blueprint of a human face, and all of the problems of GOFAI (mainly the fact that nothing is as well cut-out and defined as we would think) would surface again. For example, how do you explain that my face is primarily recognizable because of its looks, yet its looks will often greatly vary during my life without that ever affecting the fact that it is, indeed, my face.

This approach to intelligence can be summarized as recreating the learning process of new-born children after years of trying to reproduce that of a scientist.9 Meaning that what we are now building, is a capacity to ingurgitate and build connection on top of a humongous amount of pre-conceptual information. Which, as an artist, brings on the idea of creating by precisely not trying to pinpoint what it is you want to create. A precise meaning is not what you are looking for here. Not a constructed point. Not building up a very personal and singular manifestation of your subjectivity through the careful elaboration of a formal manifestation of your idea; but allowing you to go down to this sort of shapeless mass of “everything that has been made or seen”, to try and steer it towards something “never seen before, before you saw it”.10

These quotations belong to a series of texts in which Derrida talks about what it is to create, based on letters written by Antonin Artaud. In these letters, Artaud recalls (and Derrida interprets) how every creation is a betrayal of this “absolute absence, full of all possibilities”, one is compelled to go back to as a first gesture. Both Derrida and Artaud frame creating as mostly silencing any other potential creation. In this context, ML offers us a more direct than ever way of letting that absence flow. Of producing infinitely unique variations of the same in a sort of “ontologically trembling” medium.

Moreover, this atomizing poiesis, this tendency to hollow any meaning out of any cultural content and reduce it to a swarm of numbers to be crunched in amounts humans can no longer fathom, seems to come as a new reflection on the question of the authorship and the presence of the artist in the artwork. ML-based generation distributes the parenthood of the image between many elements.

After all, the dataset11 must be very carefully curated and constructed – and now too massive in scale to be humanly constituted – for the AI model to be able to produce anything convincing. Then, the technical context it is running on censors what you’ll be able to produce, and while ultimately the prompt12 sets it in motion, the stochastic nature of AI means that it is important but can’t be seen as the most defining element. And then, maybe in a deeper fashion than before because there is no intrinsic, intentional representativity here, the image needs an audience to give a cultural meaning to this probabilistic placement of numerical values as RGB layers. Which makes me consider ML as an anti-noospheric view on computation and the human mind.

The noosphere is a philosophical concept, developed by both Jesuit priest Teilhard de Chardin and biogeochemist Vladimir Vernadsky. I’m mainly referring to de Chardin’s interpretation, as it is the one I am familiar with. It is based on the idea that after the geosphere, and the biosphere, comes the noosphere, the sphere of all human cognition, that is being built and perpetually thickened by our collective intellectual activities. What interests me, in this image, is that it conveys the sense of the human intelligence as perpetually going towards more. More ideas, more complexity, more links between more complex ideas, etc. It finds an interesting echo in a lot of what digital computing, through its networking and complexifying aspects, has been about up until this point. But, as comes ML, there is a strange clash of representation in this proposition that actually, the best way to integrate and mimic a “global, planetary consciousness” as Big Tech CEOs still seem to dream about to this day, is through breaking it down to a background, computational noise.

Anderson, Sky LaRell. 2019. « The Interactive Museum: Video Games as History Lessons through Lore and Affective Design ». E-Learning and Digital Media 16 (3): 177‑95. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019834957.

Bellour, Raymond, éd. 2012. Between-the-Images. Documents / Documents Series 6. Dijon: Les presses du réel.

Czyzewski, Tytus. 1922. Zielone Oko.

Delaperrière, Maria. 2003. « La poésie polonaise face à l’avant-garde française : fascinations et réticences ». Revue de littérature comparée 307 (3): 355. https://doi.org/10.3917/rlc.307.0355.

Derrida, Jacques. 1967. L’écriture et la différence. Points Série essais 100. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Haugeland, John. 1985. Artificial intelligence: the very idea. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Penny, Simon. 2019. Making Sense: Cognition, Computing, Art, and Embodiment. Cambridge, MA : MIT Press.

Perec, Georges. 2010. An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris. Imagining Science 1. Cambridge, MA : New York: Wakefield Press ; D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers [distributor].

Smith, Brian Cantwell. 2019. The Promise of Artificial Intelligence: Reckoning and Judgment. Cambridge, MA London: The MIT Press.

Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre. 1955. Le phénomène humain. Points 222. Paris: Éd. du Seuil.

Thapa, Shaurya. 2022. « 10 Internet Creepypastas That Are Still Seriously Scary ». Screen Rant, 19 november 2022. https://screenrant.com/scariest-internet-creepypastas/.

“I use the term ‘ontology’ in its classical sense of being the branch of metaphysics concerned with the nature of reality and being – that is, as a rough synonym for ‘what there is in the world’.” Brian Cantwell Smith. 2019. The Promise of Artificial Intelligence: Reckoning and Judgment. Cambridge, MA London: The MIT Press. P.57↩

For more information on this notion of lore, and the use of item descriptions as a narrative tool, see : Anderson, S. L. 2019. “The interactive museum: Video games as history lessons through lore and affective design”. E-Learning and Digital Media 16(3), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019834957↩

Maria Delaperrière, 2003. “La poésie polonaise face à l’avant-garde française : fascinations et réticences”. Revue de littérature comparée 307 (3): 355. https://doi.org/10.3917/rlc.307.0355.↩

An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris is a 1975 short book by the French novelist Georges Perec. In a methodological writing experiment, it consists of describing all the ordinary, mundane and unremarkable things that usually go unnoticed, observed while Perec sat in Saint-Sulpice Square, in Paris, for a day.↩

Raymond Bellour, ed. 2012. Between-the-Images. Documents / Documents Series 6. Dijon: Les presses du réel.↩

Simon Penny, 2019. Making Sense: Cognition, Computing, Art, and Embodiment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.↩

John Haugeland. 1985. Artificial intelligence: the very idea. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.↩

This definition of GOFAI, as well as its ML counterpart, are both extracted from Brian Cantwell Smith, ibid, 28.↩

Brian Cantwell Smith, ibid.↩

Jacques Derrida, 1967. L’écriture et la différence. Points Série essais 100. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. P.15. My translation.↩

Designing the ensemble of images and metadata used to train a neural model.↩

In the case of text-to-image tools, the prompt designates the text the user submits to the machine.↩

“Open” is a word that originated from FOSS (Free and Open Software movement) to mean a Commons-based, non-proprietary form of computer software development (Linux, Apache) based on a decentralized, poly-hierarchical, distributed labor model. But the word “open” has now acquired an unnerving over-elasticity, a word that means so many things that at times it appears meaningless. This essay is a rhetorical analysis (if not a deconstruction) of how the term “open” functions in digital culture, the promiscuity (if not gratuitousness) with which the term “open” is utilized in the wider society, and the sometimes blatantly contradictory ideologies a indiscriminately lumped together under this word.

FOSS (Free and Open Source Software Movement), Linux, open access, Creative Commons License, copyfarleft, Telekommunisten Manifesto

“Open” is a term that has acquired an unnerving over-elasticity, a word that means so many things at times it appears meaningless. A word that originated from FOSS (Free and Open Source Software movement) to mean a Commons-based, non-proprietary form of computer software development (Linux, Apache) based on a decentralized, poly-hierarchical, distributed labor model—“open“ has now radiated its innumerable capillaries into fields as diverse as pedagogy, publishing, activism, party politics, government, science, and more. “Open“ can now mean a rhizomatic social formation that rejects top-down bureaucracy in favor of peer-to-peer network; “open“ as an insurgency against the for-profit publishing industry’s attempt to commodify knowledge (Open Access); “open“ as a Paulo Freire-like pedagogy where students are active creators—not just passive consumers—of knowledge; “open” as a form of direct democracy which rejects representative intermediaries Let‘s take a traipse through the cultural ubiquity of the term “open.“